The Duke of Wellington, the first (and only) President of the Oriental Club

In the mid-19th century, the British obsession with Indian curries and culture really started to take off (see this post for a brief history of Britain’s love of spice and India). It wasn’t just the spiciness, but the romance of the place. Queen Victoria loved the country and even had an Indian wing in the palace. Although she was the Empress of India, she never actually visited the country, leaving all that excitement to her sons.

Hanover Square in the 18th Century

Authentic – or very close approximations to authentic – curries were being made in one particular London gentleman’s club called the Oriental Club which could be found in Hanover Square. The club catered for high society – the Duke of Wellington was the President and all the chairmen seem to have been Sirs, Lords, Major-Generals or Vice-Admirals. The Club was obviously a popular one; it opened in 1825 and in 1961 it moved from Hanover Square to Stratford House on Stratford Square, where it remains to this day. If you are a Londoner (and a man), you can still join, though it does cost between £240 and £850 per year to become a member.

Stretford House, the current home of the Oriental Club

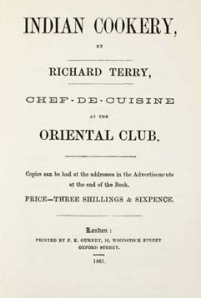

In its hey-day, Chef Richard Terry was at the helm in the kitchen, who took full advantage of the first Asian grocery warehouses; Payne’s Oriental Warehouse on Regent Street and the Oriental Depot on Leicester Square. His recipes were ‘not only from [his] own knowledge of cookery, but from Native Cooks’ too. He published a book called Indian Cookery in 1861, where the recipe below is adapted from. The job of adaptation was not done by me, but Madhur Jaffrey, though I would like to get my hands on a copy.

To make the curry, you need to make a blend of curry powder and curry paste first.

Richard Terry’s 19th Century British Curry Powder

This makes 7 tablespoons of curry powder – enough for more than three curries using the recipe below. You can of course use it in any recipe that asks for ‘curry powder’ in its list of ingredients. All the spices required are ground, but don’t buy ground coriander, pepper, cumin, cardamom and cloves if you can avoid it. Instead, roast whole spices over a medium-high heat in a dry frying pan then grind using a coffee grinder after cooling. All you need to do is mix together the following:

2 tbs ground turmeric

5 tsp ground coriander seed

2 tsp ground ginger

2 tsp Cayenne pepper

1 ½ tsp ground black pepper

½ tsp ground cumin

½ tsp cardamom seeds

½ tsp ground cloves

Store in a cool, dry, dark place.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Sir Ranald Martin’s British Curry Paste

Many old (and new!) recipes ask for curry paste, but don’t always give receipts for the paste itself. This recipe from Ranald Martin, a Victorian doctor and foodie who lived in India during the 1840s provides us with this one below. He was told it was an old Madras concoction. According to Madhur Jaffrey, the ingredients are very common in Madras, but the combination is ‘totally alien’. Aside from being used in curries, it was also used in sandwiches. The recipe below makes around 12 fluid ounces of paste.

4 tbs whole coriander seeds

2 tbs lentils such as yellow split peas or chana dal

1 tbs whole black peppercorns

1 ½ tsp whole cumin seeds

1 tbs whole brown mustard seeds

1 tbs ground turmeric

1 tbs Cayenne pepper

1 ½ tsp ground ginger

2 tsp salt

2 tsp sugar

3 cloves of garlic, minced

4 fl oz cider vinegar

6 tbs flavourless cooking oil such as sunflower or peanut oil

Dry-roast the whole spices and lentils in a frying pan until they turn a shade darker and emanate a delicious roasted aroma.

Remove from the heat, cool and grind in a spice or coffee grinder. Add the remaining ingredients except for the oil and stir well. Heat the oil in a frying pan and when hot, add the spice mixture and fry for around five minutes until the paste turns darker. Cool and empty into a jar. Store in the refrigerator.

The Oriental Club’s 19th Century Mutton Curry

Okay, you have made the paste and blended your spices, now you can get on with the curry. You can use either lamb or mutton, but bear in mind, the mutton – although more flavourful – will take longer to cook. If lamb is tricky to get hold of, goat or kid could be used as an alternative. The curry is pretty pungent, but good, dark and rich; I added a couple of peeled, chopped potatoes to add much needed-blandness. This curry serves 4 people and goes very well with plain rice, yoghurt and mango chutney. Would you believe, I forgot to take a photograph!?

4 tbs flavourless cooking oil

1 medium-sized onion, thinly sliced

2 tbs 19th Century British Curry Powder

1 tbs 19th Century British Curry Paste

1 ½ lb cubed lamb meat, shoulder is a good cut for this

8 – 12 oz (i.e. a couple of medium-sized) potatoes, peeled and cut into large chunks

¾ – 1 tsp salt

Heat the oil in one of those wide, deep frying pans that come with a lid. Add the onions and fry until the onions have browned and become crisp. Add the paste and powder, stirring well for a few seconds. Now add the meat and half of the salt, stir, cover and turn the heat right down. Gently fry for around 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add a pint of water (that’s a British pint – 20 fluid ounces) and the potatoes, turn up the heat and when the curry comes to a boil, turn the heat back down, cover and simmer very gently until the meat is tender, around 60 to 90 minutes if using lamb, longer if using mutton. Taste and add more salt if needed.

Pingback: The Jewel in the Crown | British Food: A History

My favorite Indian dish for spices, is dal, so I cooked some up to try your curry powder. I used fresh ginger and fresh tumeric, since I had them, and dumped the whole toasted, ground-up lot in with some salt in the dal, made with the tiny orange ones that cook quickly. It was delicious, though probably too strong and cried out for some fat. My garam masala recipe that I like the best is a little different. It lacks the tumeric, ginger, and cayenne, since those would be added separately, often with garlic. It adds in cinnamon, bay leaf, and fennel. Proportions can vary, but taking the 5 teaspoons of coriander you use as a standard, my recipe would have 2.5 teaspoons each black pepper, and cumin, 1 teaspoon fennel, 3/4 teaspoon cinnamon, half a teaspoon each cardamon and cloves, and a bay leaf. I have no idea where the recipe comes from, because it is on an old, old 3×5 card, written by me back in Houston. I look forward to trying the paste next! I love the spices of Indian food.

LikeLike

I too like a dal – chana dal is my personal favourite. As for garam masala I am a traditionialist: only cardamom, black peppercorns, cloves, cumin and nutmeg go in mine. Cinnamon can be added, but NEVER coriander or turmeric (says Madhur Jaffrey, and she has never done me wrong)

LikeLike

One Indian friend says that she finds that garam masala and curry powder are frequently confused in people’s minds and this is when the coriander/turmeric heresy creeps in. Mind you she says the cinnamon is heresy too.

Husband says he met a paste very much like the one above recently at a home dinner party in Delhi with okra cooked in it – the family is vegetarian. I’ve got okra plants a few inches high at the moment to try it out on – I normally use tomato to supply the acidity when cooking okra

LikeLike

It was very good, though needed ‘cutting’ with a bit of yoghurt.

I dont understand okra. It tastes nice, but then there’s all that gunge inside. I am far-from being a picky-eater, but they weird me out!

LikeLike

Pingback: Curried Beetroot Chutney | British Food: A History

Pingback: Quora

Hello there. What they eat well depends upon whether the people were upper class or simply common plebs. Your common man (or woman) would have had a boring diet of rough bread and thin porridge/soup called pottage. If really poor the bread would have been made from dried peasemeal. There would be little meat and the vegetables wouldhave been very seasonal. So the food aboard ship would definitely better than home.

Hope that answers your question…

LikeLike

Is there a digital version of the cookbook? Or does Madher Jaffery have a copy and more recipes from it?

LikeLike