Last week I was very excited to hold of some snipe, a very rare treat indeed. I roasted them and got them on my menu. To eat them in the traditional way is, by our modern standards, rather macabre; they are cooked and roasted completely whole. Guts and brain are eaten. It’s not for the faint-hearted, but, as is often the case, they make delicious eating. I was worried I had gone a little too far, but the people of Levenshulme did me proud.

So here’s a post all about snipe and how to roast and eat them in the traditional way.

A while back I wrote a general entry about game. Read it here.

Snipe in brief:

Season: 12 Aug – 31 Jan (England, Wales & Scotland); 1 Oct – 31 Jan (Northern Ireland)

Hanging time: 2-3 days

Weight: 150g

Roasting time: 10-15 minutes at 230⁰C

Breeding pairs in UK: 80 000

Indigenous?: Yes

Habitat: Mainly marshes and wetlands, but also heathland, moorland and water meadows

Collective noun: wisp (when in flight); walk (when on foot)

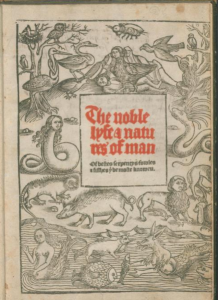

What is a snipe? Well Laurence Andrew, writing in his tome The noble lyfe and natures of man of bestes, serpentys, fowles and fishes… (c. 1527) has a pretty good stab and describing it (though I’m sure the snipe does not get its bill stuck in the mud Natural Selection would have something to say about that!):

Snyte [Snipe] is a byrde with a longe bylle & he putteth his byll in the erthe for to seke the worms in the grounde and they put their bylles in the earthe sometyme so depe that they can nat get it up agayne & thane they scratche theyr billes out agayn with theyr fete. This birde resteth betimes at nyght and they be erly abrode on the morning & they have swete flesshe to be eaten.

Weighing in at an average of 150g, the snipe is our smallest legal game bird. They are not an introduced species like the pheasant, red legged partridge or rabbit, but indigenous to the UK and Ireland (where most reside). There are around 80 000 breeding pairs in the UK, but these numbers increase substantially when around one million individuals flock to the country to overwinter.

Normally, shooting indigenous species holds up a red light for conservation – and rightly so, it should always come first, but in this case the snipe have the upper hand because they are so damn tricky to shoot.

They are secretive, highly camouflaged birds that use their very long bills to probe mud and sand flats for tasty creatures to eat. When driven at a hunt they fly in zig zags and are quickly gone again, this is why a group of them is called a wisp. (It’s no surprise, then, that especially good sharp shooters in the armed forces became known as snipers.) These birds are almost self-managing in their difficulty to hunt!

As a food they are delicious, indeed they are considered the finest eating. They are wonderfully rich and tender, and although they are small, a little goes a long way. Winston Churchill once demanded ‘a brace of snipe washed down with a pint of port’ as a hangover cure whilst on a transatlantic flight to Washington DC. Their carcasses make excellent stock.

Not just the leg and breast meat are eaten, but also the brain and the trail – in other words, the innards of the bird, usually scooped out and spread on the slice of toast it was roasted upon.

Don’t be repulsed by this! Your first worry is probably that the guts will be full of the bird’s faeces, well worry not, the snipe (and its larger cousin, the woodcock) evacuates its bowel as soon as it takes flight. Your second worry, presumably, is that you are eating gory intestines, liver, heart etc. Again, nothing to worry about here either! It is all very soft, rich and tender like a lovely warm pâté.

The head is cut in half lengthways so that the brain can removed or sucked out.

This is ancient finger food.

Sourcing snipe

As you will have guessed, finding snipe for the table is tricky. I’ve only ever seen snipe three times in butcher’s shop windows so my advice is to make friends with someone who shoots, because only a few will have been shot on any single hunt, and therefore it’s unlikely there will be any surplus for the butcher to pick up. The chances are you’ll probably have to finish the business of hanging the bird(s) yourself.

Most game birds are sold in ‘braces’, i.e. pairs, usually a cock and hen, but snipe actually come in threes, or ‘fingers’, so-called because that’s how many you can hold between the fingers of one hand.

These tiny birds do not need to hang for long, just 2 or 3 days. If it is unseasonably warm or being hung indoors 1 or 2 days should do the trick.

Preparing snipe for the table

You are to observe: we never take anything out of a wood cock or snipe

James Doak’s Cookbook, circa 1760

Snipe are extremely easy to prepare if you are roasting them:

- Pluck away the leg and breast feathers. If you like, remove the skin from its head.

- Truss the snipe with its own beak, by pulling its head down to its side and spearing the legs with its long bill.

Some recipes as you to remove the trail before you cook it (sometimes to be fried up with butter and smoked bacon). To do this, make a small incision in its vent and use a small tea or coffee spoon to remove the entrails.

Snipe can also be cooked just like any other bird if you prefer (but you are missing out on a real treat). Pluck the whole body, or peel away the skin, and cut away legs, head and feet.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Roast snipe, and how to eat it

Per person:

1 or 2 oven-ready snipe

1 or 2 pieces of toast, as large as the snipe

Butter

Salt and pepper

To accompany:

Mashed potatoes or game chips

Roast vegetables

Gravy made from game stock

A sweet jelly such as redcurrant, quince or medlar jelly

- If your snipe have been kept in the fridge, remove them and let them get to room temperature, about 30-40 minutes.

- Preheat your oven as hot as it will go, 230⁰

- Spread a good knob of butter on the toast and lay the snipe on top. Smear two more small knobs over the snipes’ breasts. Season with salt and pepper.

- Place the snipe on a roasting tin and roast for 10-12 minutes for medium-rare birds. If you are roasting several, make sure that you leave a good gap between each one so that heat can circulate around them.

- Remove from the oven and allow to rest for 5 minutes or so.

- The snipe can then be served to each guest with various accompaniments. I think it’s best if each guest carves their own snipe.

- Take the snipe off its toast and cut of its head. Use a chef’s knife the cut its head in half lengthways.

- Next, scoop out the snipe’s trail with a teaspoon and spread it over the toast.

- Remove the legs and cut away the breasts using a steak knife.

- Eating is fiddly, so use your fingers to get every piece of meat from the carcass.

- Don’t forget the brain – pick up the two halves of the head and use the beak from one half to extract the brain from the other half, then swap. Alternatively, suck the brain out.

Oh my gosh, there is never a dull moment on your blog! A perfectly ghoulish dish for Halloween :). Local eating at its best. I’m sharing this one on my facebook blog next week :).

LikeLike

ooo. thanks for sharing the post! Yes, it’s a strange one, but delicious as long as you eat with open mind (& mouth!)

LikeLike

Again, another blog which tells me about my indigenous heritage I was ignorant of. Fab in every way.

LikeLike

Gosh, thanks very much! I try my best – thanks for the comment!

LikeLike

Pingback: Woodcock | British Food: A History

Pingback: Mediæval Dining | British Food: A History