When we think of the meat that was eaten at mediaeval feasts, we conjure up images of huge pieces of roast ox, venison or wild boar’s head. There was, in fact, a wide variety of meats, especially wild birds. One of these was the grey heron and its meat was regarded very highly, only fit to serve at the top tables of a banquet; the only other waterfowl with a higher status was the regal swan. According to the late, great Clarissa Dickson-Wright, heron tastes like swan too: “it was very fishy”, she tells us, “rather stringy and reminiscent of moorhen…” It’s quite odd to think they were eaten at all; they’re such a lanky things – all neck, legs and wings. There can’t be that much meat on one.

So how does one prepare and cook a heron fit for a top table? If we look in Forme of Cury – the earliest cookbook in the English language, dating from around 1400 – and it tells us: “Cranes and herouns shul be armed with lardes of swyne, and eaten with ginger.” The “lardes of swyne” are strips of backfat or fatty bacon that are threaded through the meat so that as the lean meat cooks, the fat melts and bastes it. That’s all we get though.

We can glean more information from another book, The Boke of Keruynge or, The Book of Carving, which was written in 1513 by the splendidly named Wynkyn de Worde. He provides a long list of different animals, along with instructions on how to carve them for the table. Curiously, there are many words for carving – a specific word for each type of animal, so for a heron, you don’t just carve it, no, you “dysmembre” it:

“Dysmembre that heron.

Take an heron, and rayse his legges and his wynges as a crane, and sauce hym with vynegre, mustarde, poudre of ginger, and salte.”

(And to “Displaye” a crane, simply “unfolde his legges, and cut of his winges by the Joints.”)

So, we get am extra modicum of information: a piquant mustard sauce or glaze, but we still don’t know how it was cooked.

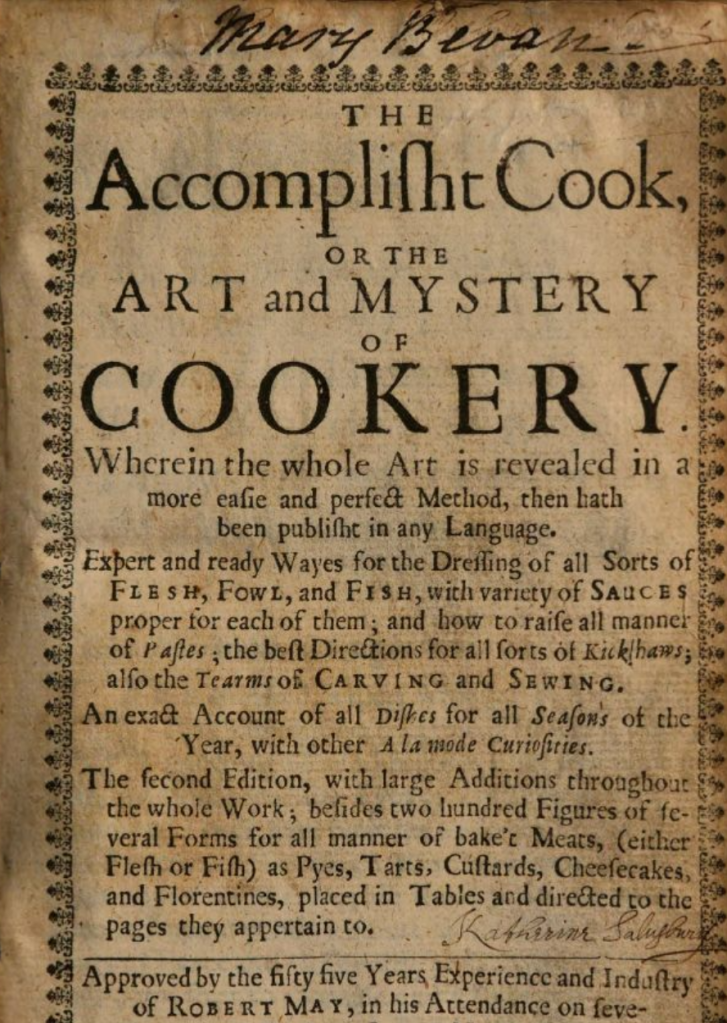

To get any detailed information, we need to go to 1660 and look at the classic tome The Accomplisht Cook by Robert May, and he had obviously read Mr de Worde’s book, because he uses the same words for carving:

“Dismember that Hern.

Take off both the legs, and lace it down to the breast with your knife on both sides, raise up the flesh, and take it clean off with the pinion; then stick the head in the breast, set the pinion on the contrary side of the carcase, and the leg on the other side, so that the bones ends may meet cross over the carcase, and the other wings cross over upon the top of the carcase.”

He also tells us that herons are not simply hunted and brought to the dinner table, but stolen from nests before they have fledged and kept in special barns

“…where there is many high cross beams for them to pearch on; then to have on the flour divers square boards with rings in them, and between every board which should be two yards square, to place round shallow tubs full of water… and be sure to keep the house sweet, and shift the water often, only the house must be made so, that it may rain in now and then, in which the hern will take much delight.”

In these sheds, the herons were not fed fish, as one might expect, but “livers, and the entrails of beasts, and such like cut in great gobbits [bite-sized pieces].” They were not just kept for the table either, many were kept for “Noblemens sports”, specifically for training their hawks. When raised for sport, they were instead fed on “great gobbits of dogs flesh, cut from the bones”

Why dogs’ flesh? Well, this was a time when Bubonic Plague was common, and at the time it was thought that dogs carried the disease, and so any strays would be routinely caught and killed. But why catch and kill an animal that you thought had plague and then feed it your own hawks? I would have thought they’d be taken to the edge of town and burned them or something, but that’s seventeenth century logic for you. CDW makes a further point: “It’s ironic when you consider that the dogs might very well have killed the rats whose fleas did carry the plague and therefore might have prevented it.”

Indeed.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

May also provides us with some recipes. In general, they are boned and filled with a minced meat and suet stuffing, seasoned with spices and oysters, then poached. Sometimes they are baked in ovens.

Herons do seem to drop out of the cookbooks after that, but they were still being eaten. The most recent reference I could find is from the 1914 book Pot Luck; or The British home cookery book by May Byron and is for Heron Pudding. It uses chunks of meat taken off the bone, and the reason why is very interesting:

“Before cooking it must be ascertained that no bones of the heron are broken. These bones are filled with a fishy fluid, which, if allowed to come in contact with the flesh, make the whole bird taste of fish.”

This may explain CDW’s issue with roast waterfowl like swan and moorhen. I wonder if they boned before cooking and if that would make them taste better?

Byron goes on:

“This fluid however, should be always extracted from the bones, and kept in a medicine cupboard, for it is excellent applied to all sorts of cuts and cracks.”

You heard it here first folks.

Heron is no longer legal game and therefore no longer eaten – as far as I know. However, if you have any stories to prove me wrong, please leave a comment, I’d love to hear about it.

References

The Accomplisht Cook (1660) by Robert May

The Boke of Keruynge (1513) by Wyknyn de Worde in Early English Meals and Manners (1868) edited by Frederick James Furnivall

Forme of Cury (c.1400) in Curye on Inglysch: English culinary manuscripts of the fourteenth century (1985) edited by Constance B Hieatt and Sharon Butler

Heron Pudding, Foods of England website: http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/Heron_Pudding.htm

A History of English Food (2011) Clarissa Dickson-Wright

Dr. Neil Buttery I’ve been trying to find an email to invite you on my podcast. I love your blog and I find your podcast on Lent so fascinating!!!! Is this a way to contact you?

Thank you Tanya Gervasi of Green World In A Pod podcast

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello! I’d love to. Yes my email is neil@britishfoodhistory.com

LikeLike

Interestingly, Richard II was served herons roasted (‘herones rostyd’) by Baron Thomas de Spencer, probably in 1397. They appear on both menus de Spencer served (see Curye on Inglysch, p. 39). These would have been spit roasted, and, as you say, probably larded beforehand. I can’t see the point in eating some of these birds but I guess much of it was about demonstrating status. Great post. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Christopher. I didn’t see that mention of the roasted herons in there. Funnily enough I read just the day after I posted that Edward III had them roasted too…

LikeLike

Oh, interesting. So quite the royal bird!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely one Neil. Yet again my grandmother has something to kick in to this discussion. I think the heron oil may have been a Fenland thing, because she’d tried it but said it wasn’t as good as mutton fat. She always kept a jar of the latter, melting in a jar on the back of the side oven, for plunging hands into before going to do outdoor work in the winter, or to apply to any chaps and cracks. She had amazingly soft hands for a woman who never had the use of a washing machine in her life. And Grandad said heron was ok in a boiled pudding if you couldn’t get anything better. But I never went into the details with him I’m afraid. He taught me to cook all sorts of fairly outre things – I can fry eels with the best – but not heron

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment Kathryn…so interesting. Though surely the heron bone fat would have smelt fishy too? Mutton obviously wins hands down!

I’m the same as you I think…I’ve fried a few eels in my time, but would probably draw the line at heron

LikeLike

Thanks for this, horrifying as it is. I just gave a Zoom talk at Vanderbilt and Kate Snyder and I reminisced on the glorious old days when we got to eat fabulous meals cooked by none other than you! Every time I poach a chicken I remember your instructions on the number of bubbles (few) that should rise through the liquid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I was some use! Haha. Kate even came to one of my pop up restaurants when she cmvisiyed the UK a while back

LikeLike

I’d love to try heron and swan, though I suspect they taste like cormorant – there’s a fabulous recipe in Countryman’s Cooking by W.M.W. Fowler.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oooo. Thanks for that! I’ve never heard of him or his book. I’ll check it out

LikeLike

It’s a fantastic book and was serialised, when republished, on Radio 4 with Leslie Philips, who was absolutely perfect for the role. It’s quite possibly still on iPlayer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll have a look-see

LikeLike

I hope it is!

LikeLike

Can’t believe you don’t have that book Neil – your youth is showing. There are lots of copies around on Abe books for half nothing so grab it quick. Swan is rather like a very big mallard in my view. Less fat and more meat than goose. And less fatty than domestic duck.

The cormorant recipe was certainly the one that made the headlines way back when. Not having tried cormorant I can’t comment. Alas it isn’t on iPlayer – Leslie Philips really was perfect. Back in the day you never knew what would turn up on the Woman’s Hour Serial – it seems to have got more serious in recent years. Well remember going out to buy The Colour of Magic after the first episode.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve obviously missed out here! I’ll have a look online for a copy…it’s obviously right up my street!

LikeLike

And I’ve just found a copy on eBay for under £4 – can’t wait for it to arrive! Thank you for the information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Which book did you get?

LikeLike

He got Countryman’s Cooking. I dug out my copy for hubby and he loved it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I need to get a copy still!

LikeLike

Pingback: Happy New Year! | British Food: A History

Petits Propos Culinaires (PPC) has a wonderful article in Issue 26 by Joop Witteveen which focuses entirely on the heron. He details information from a number of countries besides England: Netherlands, France, Germany, and Italy which discusses the preparation of herons as well as hunting and harvesting them. I was interested to read that the French (at least) considered roasted meat eaten cold to be healthier “whereas boiled meat should be eaten hot.” The section on England mentions several different sauces that should be served with herons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gosh, thanks for the information. I’ll have to see if I can get my hands on a copy of the article. Cheers!

LikeLike

Past issues of Petits Propos Culinaires (PPC) can be found at https://prospectbooks.co.uk/product-category/ppc/ . Adding to my comment about an article on herons in PPC 26, Joop Witteveen also deals with swans in PPC 24 and cranes in PPC 25. For anyone looking for additional information on food and food history, the PPC page of back issues has a search “button” where, if you type in the word(s) you are looking for, it will come up with any back issues that have an article dealing with that topic. By clicking on a suggested past PPC, there’s a list of all the topics in that PPC. I became sidetracked looking for these particular issues (24, 25, 26). I own a copy, but looking online was quicker than going through my stack one by one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great! Thanks for the links and the tip offs. I will check them out. I’d certainly like to know more about swan

LikeLike

No wonder so many falconry paintings–even well into the 19th century–depict the raptors catching herons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Make that hunting paintings in general. I just remembered that works like the one linked below are what brought me here in the first place.

https://artvee.com/dl/still-life-with-a-heron/

LikeLike

Thanks for this

LikeLike

The art site is “under maintenance”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah really? I had no idea. I shall try to find some examples.

LikeLike

Here are a couple from the 17th century:https://martin-osial.pixels.com/featured/3-the-bag-a-dead-deer-two-falcons-and-a-heron-jean-baptiste-oudry.htmlhttps://www.oceansbridge.com/shop/artists/t/te-tho/teniers-david-the-younger/heron-hunting-with-the-archduke-leopold-wilhelm-1652-56

And one from Landseer:https://islingtongovuk.j2bloggy.com/Futurezone2020/week-2-art-landseer/?doing_wp_cron=1661414514.8969259262084960937500

LikeLike

Well I just ate some heron and I can say that it is pretty good. Being a fish-farmer, a colleague, on a different farm in our group at which herons are problematic, has permission to shoot a certain number per year, and I took one home with me. I took its breasts off , sliced, and shallow fried them. It’s reminiscent of pigeon but has a curious rich buttery-like flavour. I did this as I had been told that it was good eating by another fish-farmer, who has also tried cormorant2 which he assures me is utterly disgusting. I definitely wouldn’t mid trying swan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whoa! I’m so glad it was delicious. Thanks for letting me know – if you get hold of a swam, I’ll come round!

LikeLiked by 1 person