Hello everyone! It’s been a while hasn’t it? My apologies but getting the book ready for handing in took rather longer than expected.

I thought I’d break the ice with a post all about the pressure cooker – an odd subject to choose, you may think, but bear with me, for it has a particularly interesting genesis. (Also, I recently received one from my sister-in-law.)

Pressure cookers are ingenious things because they cook food much more quickly than regular saucepans or stockpots, and this is because the food – usually a stock or casserole – is cooked under high pressure and therefore a higher temperature. A regular pot of water boils at 100°C, but cannot reach a higher temperature because the water becomes steam, boiling away into the ether. However, place a sealed lid on top, the steam – a gas – cannot escape and consequently pressure builds up in the air space within the cooker. Because the steam it at high pressure, it’s harder for water to enter the gaseous phase, and it requires more energy to do so, effectively raising the boiling point. Inside a domestic pressure cooker, water boils at 120°C (around 2 atmospheres of pressure), and reduces the cook time by as much as 80%.

Until recently, I was a bit dubious about cooking in this way, because whenever I make stock, or slowly braise some meat, I bathe the meat and vegetables in water or stock at around 80°C, I don’t boil them; that usually results in tough meat and a lot of scum. Not good. The thought of cooking something at 120°C and having something tender as a result, seemed unintuitive, but I was wrong, tenderness is expected; in fact some “gourmets” are of the opinion that the meat is too soft and cannot “replace the traditional method of simmering.”

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this post for more information.

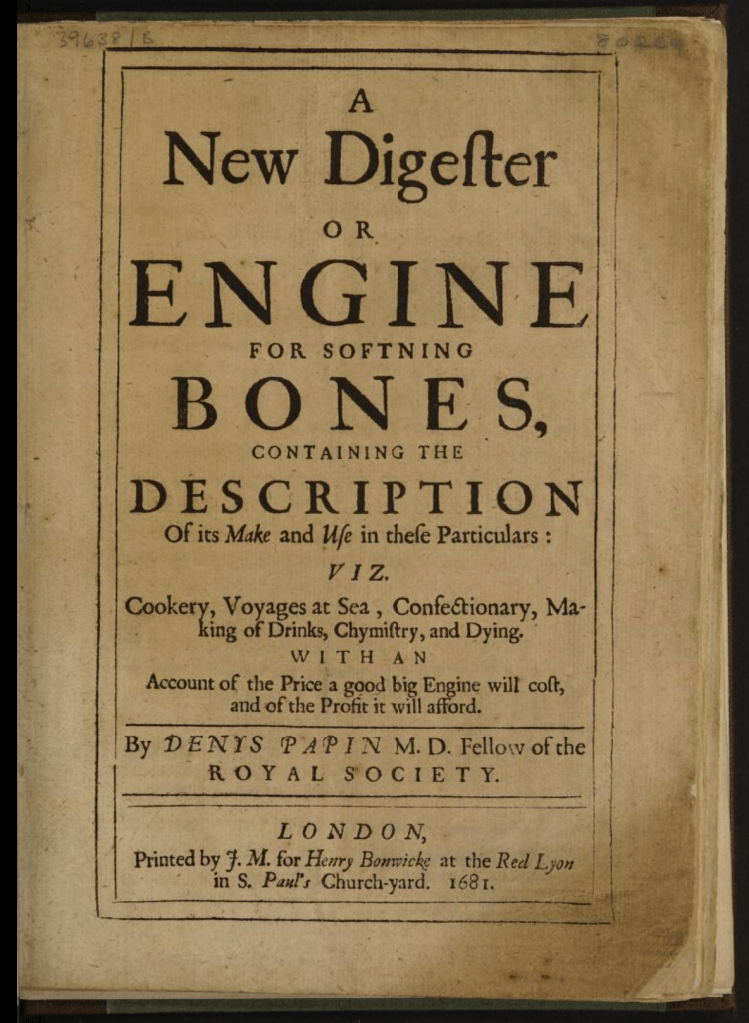

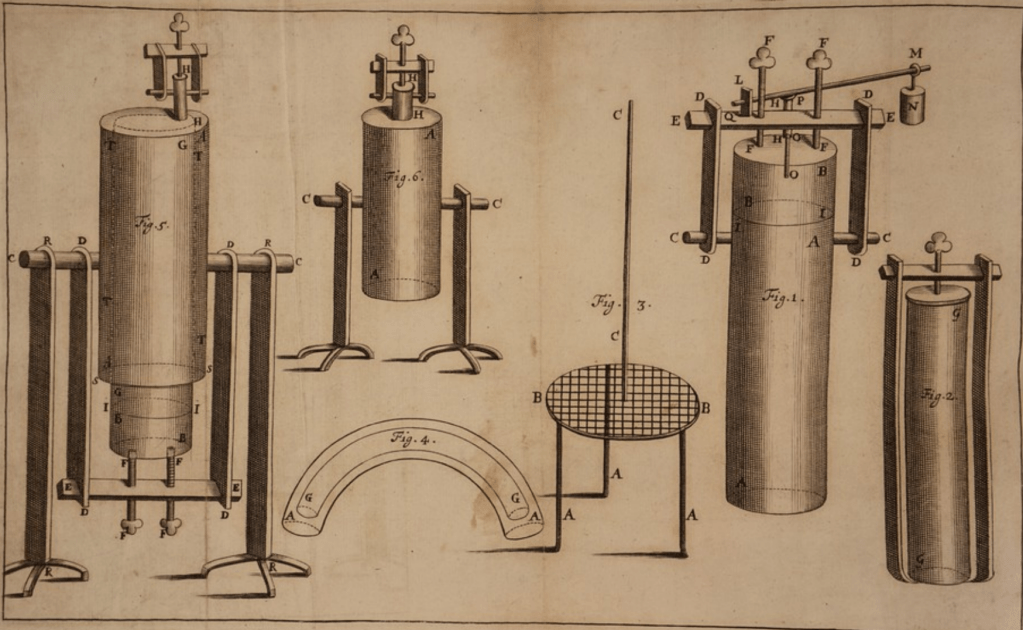

Its origin story goes right back to the 17th century. French physician Denis Papin invented his ‘Digester’, as he called it; a large cylindrical sealed chamber, heated over coals able to reach pressures of eight atmospheres (boiling point around 175°). He presented it to the Royal Society in 1679; amongst the fellows were luminaries such as Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke, and so impressed were they that they commissioned his book A New Digester or Engine for Softening Bones in 1681. The next year, he cooked the Society a Digester dinner. Present at the meal was the great diarist and champion of salads, John Evelyn, who later wrote:

12th April, 1682. I went this afternoon with several of the Royal Society to a supper which was all dressed, both fish and flesh, in Monsieur Papin’s digestors, by which the hardest bones of beef itself, and mutton, were made as soft as cheese, without water or other liquor, and with less than eight ounces of coals, producing an incredible quantity of gravy; and for close of all, a jelly made of the bones of beef, the best for clearness and good relish, and the most delicious that I had ever seen, or tasted. We ate pike and other fish, bones and all, without impediment…the natural juice of all these provisions acting on the grosser substances, reduced the hardest bones to tenderness…I sent a glass of the jelly to my wife, to the reproach of all that the ladies ever made of their best hartshorn.

So it seems that Evelyn not only confirms that cooking under pressure makes meat – and even bone – exceedingly tender, but also that it is a very good thing.

As good as it may be, that it was invented in the first place seems rather odd – why build a machine for softening bones? Papin makes his objective very clear: “no body can deny that…by the help of the Engine here treated thereof, the oldest and hardest Cow-Beef may be made as tender and as savoury as young and choice meat.” Cheap cuts that cost little but require a lot of fuel to cook tenderly, were suddenly quick to prepare and very pleasurable to eat, and he knew that this had huge implications for the working poor, and the improvement of their scant, and often miserable, diet.

Papin was very influential as part of the Royal Society, and worked alongside Robert Boyle, assisting him in his experiments exploring the nature of pressure, the result of which being Boyle’s Law. It wasn’t long before someone realised that his Digester had potential beyond the softening of bones: “all you need to do is attach a piston and you have begun to produce a steam engine.”

The Digester as a piece of cooking equipment did not take off – it was expensive to build and could be rather dangerous. It wasn’t until the addition of safety valves that effectively stopped the pressure from getting too high, and safety locks preventing the lid from flying off if opened too soon, would it become more common. This would take a while, and domestic pressure cookers only became available in Britain from 1949 where they were “hailed with delight”. The cookers were still prone to exploding, and they still wouldn’t become very popular until the 1970s when safety legislation was tightened further.

Today, pressure cookers are very safe and are very easy to use; though I do admit I was a little worried using one for the first time. With a pressure cooker, a rich beef stock can be made in 2 ½ hours rather than 12, making stock-making suddenly economically-viable. This fact convinced me to give it a go. After a quick rummage in the freezer, I found not beef bones but hogget bones, leftover from the legs I roasted for the podcast and Grigson blog last year (see here and here). The resulting stock was magnificent – richer and more delicious than any meat stock I had cooked before. Then, I tested it out on some pigeons, cooking them pie-style just as John Evelyn had mentioned in his diary, but you’ll have to wait until the next post to hear about that!

References

A New Digester or Engine for Softening Bones (1681) by Denis Papin. Available to view at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/heyqybu9

The Diary of John Evelyn Volume II (1665-1706) by John Evelyn. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/42081

The Instant Pot of the 1600s Was Known as ‘the Digester of Bones’, Atlas Obscura website (2018): https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/who-invented-the-instant-pot

Larousse Gastronomique (2001)

Marguerite Patten’s Century of British Cooking (2015) by Marguerite Patten

On Food and Cooking, Second Edition (2007) by Harold McGee

I’ve used various pressure cookers over the years but Prestige take some beating. My present one is a Prestige Hi-Dome of 1955 vintage. Still as good as new and plenty of spares to be had. I can never understand folk who use micro waves. Pressure for me always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

1955? That’s pretty good. I feel like such a rookie!

LikeLike

I think you would enjoy my eclectic collection of kitchen equipment. A few go back to Victorian times. My English Electric cooker is 64 years old and shows no sign of giving up.

LikeLike

Ooo. Yes Victorian kitchenalia is great!

LikeLike

Alas, my brother inherited the parental high dome. A lovely cooker. I have to make do with a Kuhn Rikon that is only 30 years or so old.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apparently it’s density rather than temperature that’s the key to reducing cooking time. Who knew!?! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really? My little brain can’t handle that much physics!

LikeLike

There’s a beautiful passage in Dorothy Hartley where she’s reminiscing about the kitchen of her convent school in the evening, with the ordinary stock pot scrubbed and lying on its side to dry, the cat sleeping by the hearth, and the digester clucking on the back of the range. It’s an image that has stayed with me since Food in England was first published

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I remember that now you’ve said it. I can’t believe I forgot about Hartley when researching this! I might root it out for the follow-up post I’ll be writing for next week

LikeLike

Pingback: Pie-Style Pressure Cooker Pigeon | British Food: A History

Pingback: Jackpot Readiness: The (Literal) Pressure Cooker | naked capitalism

Pingback: Jackpot Readiness: The (Literal) Pressure Cooker | naked capitalism

Pingback: Jackpot Readiness: The (Literal) Strain Cooker - TheBestEntrepreneurship

This is a very amazing.

LikeLike

Pingback: Happy New Year! | British Food: A History