Some original text from the Form of Cury – a recipe for blank mang (British Library)

The Forme of Cury (literally, A Method of Cookery) is Britain’s earliest known cook book, dating from around 1390. Regular readers will know, I am somewhat of a mediaevalist and so I have leafed through this ancient text many times, slowly soaking up the recipes just like a sop in potage.

The effort required to produce the food, prepare it an obtain the ingredients, the surroundings and equipment and the wonderment of a mediaeval feast are all there to see, but from one person’s perspective: the cook.

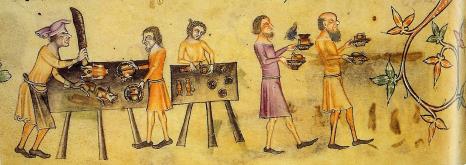

Angry Cook and Waiters c. 1330

By cooking recipes from books like this, we get a glimpse of a bygone world, and with a bit of knowledge about the ingredients and methods used to prepare them, you get to experience history almost at first hand and really fires up the imagination. Anyone with as passing interest in history will love giving recipes like this as go, and I implore you to try, whether it be this book, or something more accessible like Mrs Beeton’s Book of Houshold Management, you won’t be disappointed.

Of course, for the Forme of Cury you have to brush up on your Middle English – this is the language of Chaucer – but with a good glossary and some persistence, you will tune in.

The Forme of Cury begins thus:

The Forme of Cury was compiled of the chef maister cooks of kyng Richard the Secunde king of Englond aftir the Conquest.

Richard II, the Dandy King, was flamboyant and ostentatious; he lived in grandeur and was considered to be a narcissistic, effeminate fop by many. Everything was done on a grand scale. His court and household were huge: 200 personal guards, 13 bishops, barons, knights, esquires plus many servants and other workers. In all, around 10 000 people worked under him.

Richard’s feasting and partying were also elaborate – one feast in 1383 cost 57 000 pounds plus an extra 10 000 pounds for napery and spices! If he were alive he’d be called a foodie for sure, his other gift to gastronomy aside from this book, being the napkin, prior to that the tablecloth doubled as one.

Richard was also obsessed with record-keeping, and because of this he commissioned this manuscript, and history is all the much richer for it.

Richard II

Who wrote it?

The master cooks will not have written the recipes down themselves, it’s very likely that they were illerate, but they will have been dictated to by a scribe who sat behind the master cook taking notes. The cook himself sat in a raised chair in the centre of the huge kitchen, filled with industrious workers such as the bakers, the sauce cook, the spit-roaster, and the mincer; there was even a person in charge of salad! From his chair he was lord of all he surveyed, checking every dish before it was ‘served forth’.

The manuscripts

There are ten incomplete copies of the Forme of Cury in existence today, but the original 1390 document seems to be forever lost. The most complete copy is a six-metre long scroll of vellum parchment which is housed in the British Museum. No extant copy matches up exactly and all appear to contain errors or omissions (and in some cases additions). These differences are mainly due to human error by copying – some scribes were better than others it seems – but some are purposeful, new recipes unique to the commissioning household could be added, and some removed if disliked.

The Forme of Cury scroll (British Museum)

These manuscripts were transcribed and published as printed documents several centuries later many containing further errors, but they are invaluable because the text is easier to read, and many were written before some of the original copies degenerated, becoming unreadable. Some errors were mistranslations, for example ‘cast’ being swapped for ‘yeast’ (which was then spelt ȝast); other mistakes were made because non-cooks were doing the translating. In one case one transcriber recommends pouring boiling hot water over an intricately constructed pastry castle – not a good idea!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

The recipes

Modern editions of the book start with a list of recipes, and such a breadth of dishes is represented. Some are homely, many are ostentatious, others mysterious. There are some familiar names and ingredients: blancmange, custard tart, soups and stews, gruel and frumenty and hippocras (spiced wine), all of which would go down well at a dinner party today. However, I’m not sure if porpoise in frumenty or piglets in sage sauce would be well-received.

Excerpt from a modern transcription of the Forme of Cury

On feast days there was a type of dish called a sotielty (subtlety) which was not eaten, just looked at. Examples include the aforementioned pastry castle; the cokagrys, a half-pig, half-cock creation, and animals on pilgrimage, dressed in clothes and holding lamprey staffs.

The food that was eaten, however, was similarly painstaking to produce. To show of Richard’s great wealth there would be liberal use of spices and sugar (which was then considered a spice) as well as dried fruits such as currants, which had to have their seeds individually removed before they could be used – there was no such thing as seedless grapes in the 14th Century!

There were more fast days then feast days however, so there are many vegetarian and vegan dishes as well as recipes using freshwater fish and almonds or almond milk.

Some recipes are familiar and are delicious (they made great custard tarts), there are early recipes for rice pudding, bread sauce and meatballs. They even made pasta, which was most often rolled out thinly, cut into diamonds and dried. The pasta would be layered up with cooked mincemeat and a cheese sauce: in other words, a mediaeval English lasagne!

Food from The Forme of Cury has appeared on the blog before (see the Tartlettes post) and I made eel pie and hippocras for Alice Roberts on Channel 4’s Britain’s Most Historic Towns. I’ve waffled on a bit so I’ll post some original recipes as well as my interpretations of them in the next few days.

Pingback: Favourite Cook Books no. 3: The Forme of Cury, part 2 – recipes | British Food: A History

Pingback: Macaroni Cheese | British Food: A History

Pingback: Medieval Rose Pudding (Rosee) | British Food: A History

Pingback: Lent podcast episode 2: Fish & Humours | British Food: A History

Pingback: Blue Cheese Ice Cream with Poached Pears | British Food: A History

Pingback: Manchets and Payndemayn | British Food: A History

Pingback: Forgotten Foods #10: Porpoise | British Food: A History