A. Cook’s Perspective is an investigation into the work of the rather obscure and eccentric 18th-century cook and cookery writer Ann Cook, her methods and her infamous hatred of the popular cookery writer, and her contemporary, Hannah Glasse and her book The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. The book is essentially a transcript of Cook’s Professed Cookery garnished liberally with comments and insights into Ann and Hannah’s recipes, their cooking methods as well as Ann’s state of mind. The book is authored by experienced food historians and historical cooks Clarissa F. Dillon and Deborah J. Peterson who investigate Cook’s spleen-venting by cooking her and Hannah’s recipes to understand whether Cook’s vitriolic take-down of Glasse has any grounding.

A. Cook’s Perspective is a very useful book – firstly because it’s an edited transcription of Cook’s work (including her bizarre preface which attacks Hannah Glasse in rhyming couplets and long-form poetry) which is very handy for those who prefer to read a book over a digitised PDF. But the book adds so much more than that because Dillon and Peterson really get to work on fact-checking and inspecting the minutiae of Cook’s methodologies by making the recipes themselves – and it’s a mixed bag, sometimes landing in favour of Cook, other times Glasse. Their work also exposes Mrs Cook as a vindictive, petulant, embittered woman, and it gives this reader more insight into the bizarre one-sided acrimony (it is unknown whether Hannah Glasse ever met, or even knew, Ann Cook) which I had previously thought was generally in agreement of Cook’s assessment. The reality is – as usual – much more complex. Having a physical book in my hand allowed me to read Cook’s work more closely (something difficult to do when reading digitised texts online), and it shed light on the evolution and pedigree of some dishes. For example, I spotted elements of Cook’s recipe ‘To make a White Fricassey of Rabbets’ in Elizabeth Raffald’s recipe ‘Rabbits Surprized’, a dish I thought to be totally unique to Raffald.

Dillon and Peterson’s approach of writing comments beneath original prose is a good one: it helps us to understand how some recipes work, and how the writers go about interpreting them. They also demonstrate the importance and benefit of cooking the recipes oneself, rather than simply reading them. There are several occasions too where the authors are at a loss as to Ann’s meaning or point in some of her comments, many of which seem to be nonsensical or simply ‘whining’. By criticising Ann Cook’s own criticisms we do glean an extra layer of understanding of 18th-century cooking.

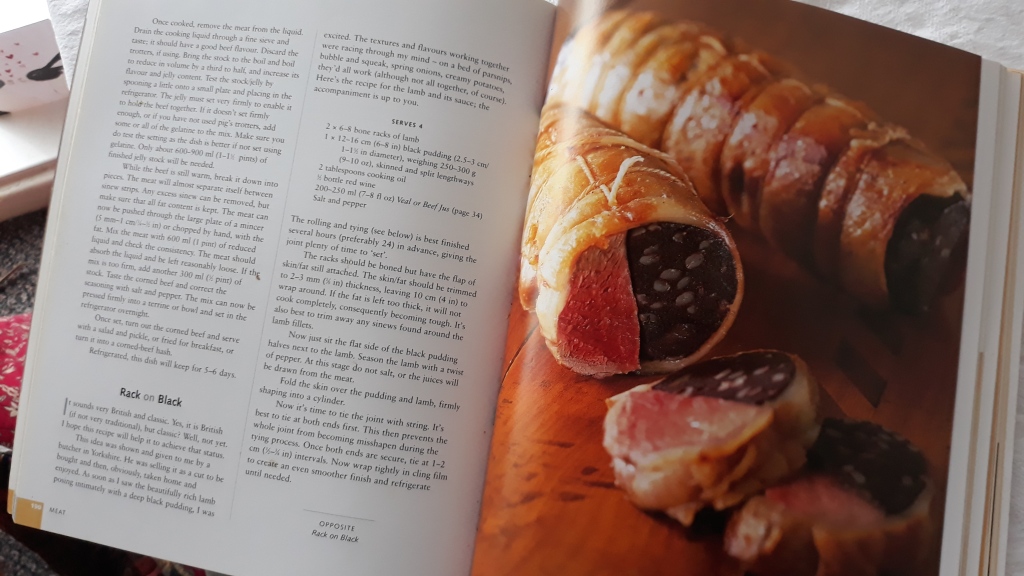

As someone with an interest in the cookery writers of the 18th century, I would have liked to have seen the introduction, i.e. the backstory, fleshed out a lot more: the two ladies’ biographies, achievements and inter-relatedness. Photos of the food would have helped bring the dishes to life, as would some images, say contemporary artwork, of 18th-century foods being served or prepared.

Overall, A. Cook’s Perspective is a worthy addition to the home library of anyone interested in 18th-century cookery because it provides us with practical knowledge of cooking at this point in history, but it also gives us an almost voyeuristic view of Ann Cook’s psyche and her deep-seated, intense dislike of a cookery icon at a time when the personal thoughts and feelings of female cookery writers are so rarely captured.

A. Cook’s Perspective: A Fascinating Insight into 18th-century Recipes by Two Historic Cooks by Clarissa F. Dillon & Deborah J. Peterson is out now and is published by Brookline Books.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce and would to start a £3 monthly subscription, or would like to treat me to virtual coffee or pint: follow this link for more information. Thank you.