I have now cooked all 16 recipes in the Lamb & Mutton section of English Food by Jane Grigson!

There were highs, there were lows. And there was lamb’s head in brain sauce. It had it all. Read my review of the section on the other blog Neil Cook Grigson.

Section 4.2 of English Food, Lamb & Mutton, Completed!

Filed under Uncategorized

Toad-in-the-Hole: History & a Recipe

Toad-in-the-hole is a stone-cold classic British dish, and one I make often. It occurred to me recently that I’ve never written up my recipe, so I thought I should rectify this! It is considered by other nations to be one of those ‘weird’ British foods – I’ve no idea why, it’s roasted sausages in a Yorkshire pudding. What’s not to like? Do folk think there is a real toad in there?

Well, naysayers, don’t knock it till you’ve tried it: it’s a delicious, simple, hearty and economical pleasure, as most British food is, and I think it is a meal most Brits would rate very highly. It wasn’t always the case, as Jane Grigson points out in English Food, the ‘toads’ were pieces of leftover boiled or roasted meat or poor quality sausages which ‘gave Toad-in-the-Hole a bad name as one of the meaner English dishes.’[1] Economical should never be made equivalent to mean.

Looking into the history of toad-in-the-hole presents us with a quandary, because it is rather difficult to pin down when it first appears in print. Why? Well, it depends on your criteria. Let’s start with what is widely regarded to be the first recipe with that name (well, actually it’s called toad-in-a-hole, but let’s not split hairs), which crops up in Richard Briggs’ The English Art of Cookery, published in 1788:

Mix a pound of flour with a pint of and a half of milk and four eggs into a batter, put in a little salt, beaten ginger, and a little grated nutmeg, put it into a deep dish that you intend to send it to table in, take a veiny piece of beef, sprinkle it with salt, put it into the batter, bake it two hours, and send it up hot.[2]

So, here we have a single large toad in the form of a piece of beef. This makes sense; the dish is called toad-in-the-hole, not toads-in-the-hole. In The Tavern Cook, Marc Meltonville does make the point that it is baked,[3] which is important because the earliest mention of toad-in-the-hole actually comes the year before in Francis Grose’s Provincial Glossary, where it is described as ‘meat boiled in a crust’.[4] Are either of these really toad-in-the-hole recipes? There is a better contender in my book. It’s not a recipe, but a good description of one, and it can be found within the pages of the diary of shopkeeper Thomas Turner, dated Saturday, 9th of February 1765:

I dined on a sausage batter pudding baked (which is this: a little flour and milk beat up into a batter with an egg and some salt and a few sausages cut into pieces and put in it and baked)…[5]

This – I hope you agree – is a modern toad-in-the-hole in all but name!

We can go even further than this: some food historians think that the original recipe actually goes back another 20 years to Hannah Glasse’s 1747 classic The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.[6] The recipe is for ‘Pigeons in a Hole’. Here, pigeons are buttered and seasoned, popped into a dish and a batter is poured over them and baked.[7] Is this the winner? Well it all depends what you are counting as toad-in-the-hole, of course, but I hope this gives you an overview of the dish’s evolution.

In the 19th century, various other ‘toads’ were used: Mrs Beeton gives recipes using beef steak and pieces of kidney. She also suggests adding mushrooms or oysters, and also recommends using leftover, underdone meat.[8] According to Sheila Hutchins, even whole, boned chickens have played the part of the toad.[9] I must say that this sounds most appealing!

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the Easter eggs, a monthly newsletter and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

Recipe

I used my 10-inch Netherton Foundry Prospector Pan throughout because it can be used on the hob and in the oven. It’s also round, which makes portioning much easier when it comes to serving time. The amounts given for the batter are the same as for my Yorkshire pudding recipe, so you could make the toad-in-the-hole in a rectangular tray or even a sturdy cake tin. Colour the sausages in a frying pan first and then transfer them to your chosen receptacle!

¾ cup/180 ml plain flour

½ tsp salt

¾ cup/180 ml eggs (around 4 medium eggs)

¾ cup milk

60 g beef dripping or lard, or 60 ml sunflower or rapeseed oil

6 good quality sausages

Mix the flour and salt together, make a well in the centre and add the eggs. Beat well until smooth, then beat in the milk. Set aside for an hour (you don’t have to do this, but you do get a slightly better rise this way).

Preheat your oven to 230°C.

Heat a little of the fat or oil in your pan and brown the sausages on two sides: you’re not looking to cook them, just to sear them, as it were. Remove the sausages and set aside.

Add the remaining fat to the pan or tray in which you’ll be baking the toad-in-the hole (along with any juices from the frying pan, if used), place in the oven and allow it to become very hot and smoking– a good 15 minutes. Gingerly remove the pan or tray and add a ladleful of batter to it, and give it a quick swirl before returning it to the oven to cook and set for 3 or 4 minutes.

Remove the pan or tray, arrange the sausages evenly and neatly and pour over the rest of the batter. Return to the oven. Do all of this as quickly – and safely – as possible.

Bake for 30 minutes until well risen and a deep-golden brown. If the pudding and sausages are going a bit too brown for your liking, turn the heat down to 180°C.

Serve with plenty of onion gravy, steamed vegetables and a blob of mustard.

Notes

[1] Grigson, J. (1992). English Food (Third Edit). Penguin.

[2] This is Marc Meltonville’s transcription from his 2023 book The Tavern Cook: Eighteenth Century Dining through the Recipes of Richard Briggs published by Prospect Books

[3] Ibid.

[4] Grose, F. (1790). A provincial glossary: with a collection of local proverbs, and popular superstitions (2nd ed.). S. Hooper.

[5] Turner, T. (1994). The diary of Thomas Turner, 1754-1765 (D. Vaisey, Ed.). CTR Publishing.

[6] One of the food historians in question is Alan Davidson, in The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press (1999).

[7] Glasse, H. (1747). The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. Prospect Books.

[8] Beeton, I. (1861). The Book of Household Management. Lightning Source.

[9] Hutchins, S. (1967). English Recipes, and others from Scotland, Wales and Ireland as they appeared in eighteenth and nineteenth century cookery books and now devised for modern use. Cookery Book Club.

Robert Burns, the Globe Inn & Annandale Distillery with Jane Brown, Teresa Church & David Thomson

Welcome to the second of a two-part podcast special all about Burns Night.

Burns Night, celebrated on Robert Burns’ birthday, 25th January, is a worldwide phenomenon and I wanted to make a couple of episodes focussing upon the night, the haggis, but also the other foods links regarding Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns.

So, if you’re readying yourself for a Burns supper, I hope this episode gets you even more into the celebratory spirit. If you’re not marking Burns Night? Well, hopefully after listening to this, you will be inspired to get yourself some haggis, neeps, tatties and a dram of whisky.

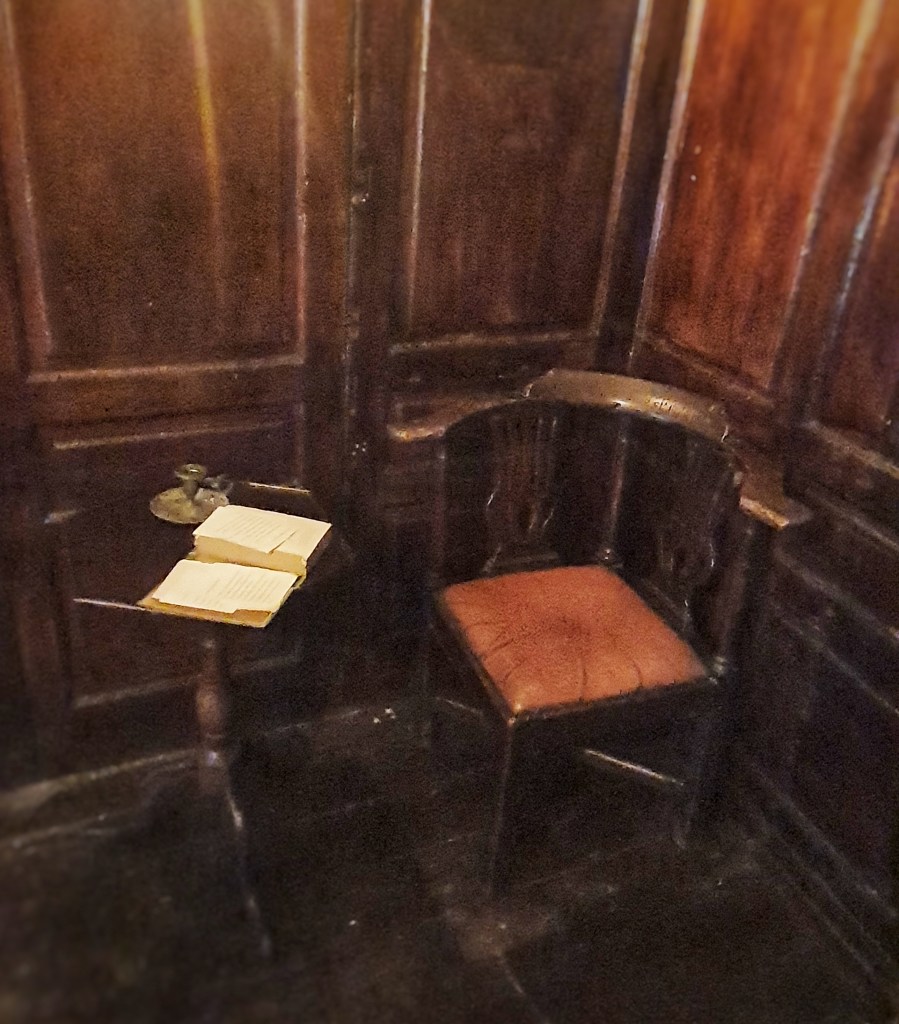

Today’s episode is a jam-packed one where I speak with three guests all about Robert Burns and his links with Dumfriesshire, Southwest Scotland. First of all, I speak with Jane Brown, Honorary President of the Robert Burns World Federation, and ex-manager of The Globe, Robert Burns’s favourite haunt when he lived in Dumfries during the last eight years of his life. Jane has attended and spoken at many Burns Nights all over the world, so there’s no one better to talk about with Burns’s life, which had several links with food and drink: there’s Burns Night and the Address to a Haggis, his time as an exciseman and as a farmer, and his time at the Globe. Then there’s the Globe itself and all of the precious artefacts contained within it that have been painstakingly conserved by owners Teresa Church and David Thomson.

The British Food History Podcast is available on all podcast apps and now YouTube. You can also stream it via this Spotify embed below:

David and Teresa also own the Annandale Distillery, which produces a delicious and unique single malt whisky. It’s available unpeated and called Man O’Words, after Robert Burns, and the other is peated and called Man O’Sword, after the other local historical figure associated with Dumfries, Robert the Bruce. Like the Globe, the old distillery was saved, beautifully conserved and brought back to life by David and Teresa.

In today’s episode, we talk about Burns’s before and after graces, Burns’s penchant for scratching poetry on inn windows, the importance of cask size on the flavour of whisky, and just what exactly possessed David and Teresa to buy the Globe and a falling-down distillery in the first place – amongst many other things.

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food, please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or leave a comment below.

The Robert Burns World Federation

Follow 1610 at the Globe on social media: Instagram @theglobeinn1610; Facebook https://www.facebook.com/theglobeinn/?locale=en_GB; X @The GlobeInn1610

Follow Annandale Distillery on social media: Instagram: @annandale_distillery; Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/annandaledistillery/?locale=en_GB; X: @AnnandaleDstlry

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the Easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

Article: Local whisky maker hailed for its ‘world class’ and ‘immaculate’ malt at top awards. From in-Cumbria

Annandale Distillery on Visit Scotland website

MMR website (David and Teresa’s day job!)

David’s article about the importance of cask size when maturing whisky

My ‘Taste of Britain’ series in Countrylife Magazine

Previous pertinent blog posts

Previous pertinent podcast episodes

Haggis and the First Burns Suppers with Jennie Hood

Neil’s blogs and YouTube channel

The British Food History Channel

Neil’s books

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper

Chicken Balmoral

Chicken Balmoral is a modern British classic: a chicken breast stuffed with haggis, wrapped in bacon and then either oven-roasted or pan-fried. It’s served with a rich whisky cream sauce. You can’t stuff a great deal of haggis into a chicken breast, so I find it a great way of using up leftover haggis after a Burns supper. It’s also a great dish to serve up to those uninitiated in the pleasures of the Chieftain of the Pudding Race.

If you want to know more about Robert Burns, the first Burns suppers and the history of this haggis, listen to the first part of my two-part Burns Night specials on The British Food History Podcast:

Despite its name, chicken Balmoral isn’t particularly old; it sounds like it should be Victorian, it being named after Queen Victoria’s beloved Balmoral Castle, nestled in the beautiful Cairngorms. But, no, it is most definitely a 20th-century invention – the earliest mention I could find of a dish called chicken Balmoral is in the 1928 publication A Book of Empire Dinners (published by the Empire Marketing Board of Great Britain), but it is only a mention, not a description.1 It is also conspicuous by its absence from F. Marion McNeill’s The Scot’s Kitchen, which certainly tells us something about its position in traditional Scottish cuisine.2 As Ben Mervis put it in The British Cook Book ‘[it] seems a little too cute – a little too on the nose – to be a truly traditional Scottish dish.’3

It seems to me that it is a dish created for restaurant service; the use of a prime cut, the fact that most of the prep can be done well ahead of time, and that there is next to no waste, all certainly point to the fact. It does, however, make chicken Balmoral an excellent dish for a dinner party. You won’t be slaving over a hot stove making this meal, that’s for sure.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription, where you will receive access to the secret podcast, a monthly newsletter and other premium content: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

Chicken Balmoral is “traditionally” served with seasonal vegetables; however, for my version, I chose to eat it with the classic Burns Night supper companions of mashed neeps and tatties – i.e. mashed swede and potatoes.

Serves four, but it can be very easily proportioned for more or fewer folk.

For the chicken

3 tbs flavourless cooking oil, lard or bacon fat (or a mixture)

Around 160 g leftover haggis

4 chicken breasts

16 rashers of dry-cured streaky bacon

For the whisky sauce

30g butter

½ onion or the white part of a leek, thinly sliced

3 to 4 tbs whisky

150ml very hot chicken stock

100ml double cream

Salt and pepper

Preheat your oven to 200°C. Add the fats and/or oil to a roasting tin and place on the middle shelf to get really nice and hot.

Lay the chicken breasts smooth side down on a chopping board. Move the tender out of the way (it’s sometimes partially attached and can get in the way). Press a breast down firmly with the palm of your hand, and, using a small, sharp, pointed knife, cut into the thick end of the breast as far as you can without puncturing the breast as it tapers toward the end. Widen the hole slightly – it needs to be about 2 centimetres wide at the mouth. Repeat with the other three breasts.

Divide the haggis into four equal pieces and roll each piece into a sausage shape, thin enough to insert into the chicken. Some haggises are quite crumbly, but don’t worry if they are not pliable enough. Use your forefinger to force the haggis into the cuts in the breasts. You might find it easier to break the haggis into smaller pieces.

Take four rashers of bacon and lay them across your chopping board lengthways, so that they overlap just slightly. Lay the chicken breast perpendicular to the bacon rashers and roll it up so that the join is underneath the chicken breast. Trim away excess bacon. Repeat with the remaining chicken breasts.

By now, the fat or oil will have become very hot indeed. Take the tin out of the oven (careful!) and sit the breasts in the hot fat, thin ends pointing inwards (this ensures they don’t overcook). Place in the oven for the oven for 30 – 35 minutes, turning it down to 180°C after 15 minutes. Baste at least twice whilst they cook. Remove and allow to rest on a plate.

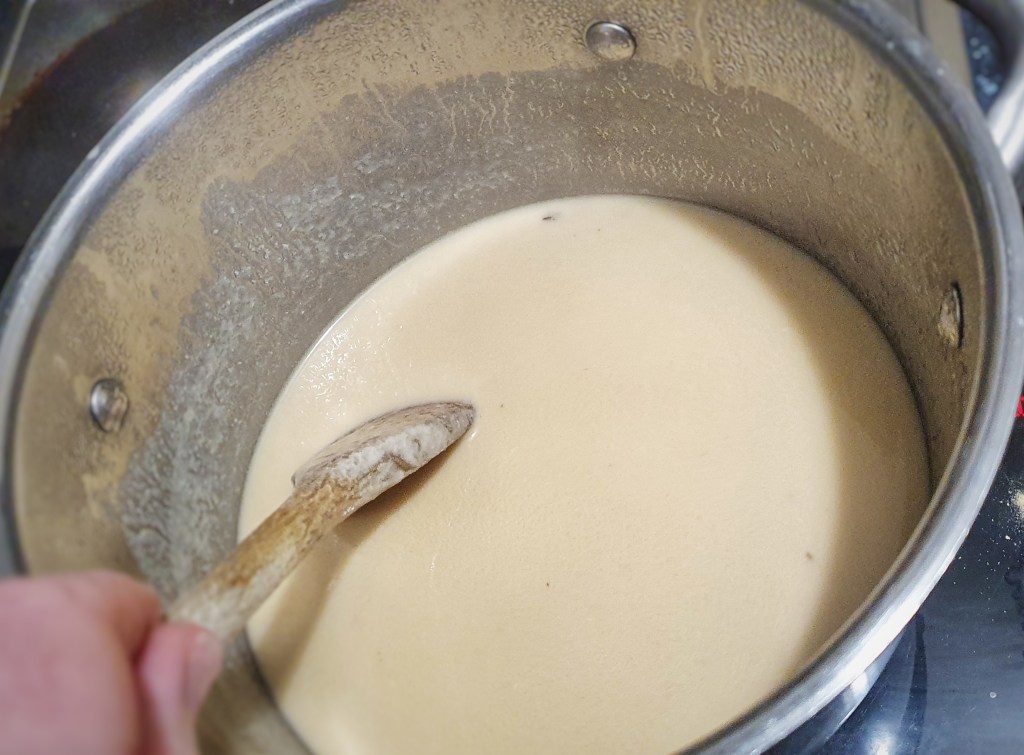

Meanwhile, make the sauce: melt the butter in a saucepan and fry the onion or leek until soft, but not browned (this will take around 8 minutes) before adding three tablespoons of the whisky. Pour the excess fat from the roasting tin and deglaze it with the chicken stock. Scrape all of the nice salty burnt bits with a wooden spoon and cast them into the saucepan. Simmer for a further five minutes before passing through a sieve into a clean saucepan. Add the cream, heat to simmering point and season to taste with salt, pepper and more whisky (if needed).

Serve the chicken with mashed neeps and tatties and pour the sauce into a warm gravy boat.

References

1. A Book of Empire Dinners. (Empire Marketing Board, 1928).

2. McNeill, F. M. The Scots Kitchen: Its Lore & Recipes. (Blackie & Son Limited, 1968).

3. Mervis, B. The British Cook Book. (Phaidon, 2022).

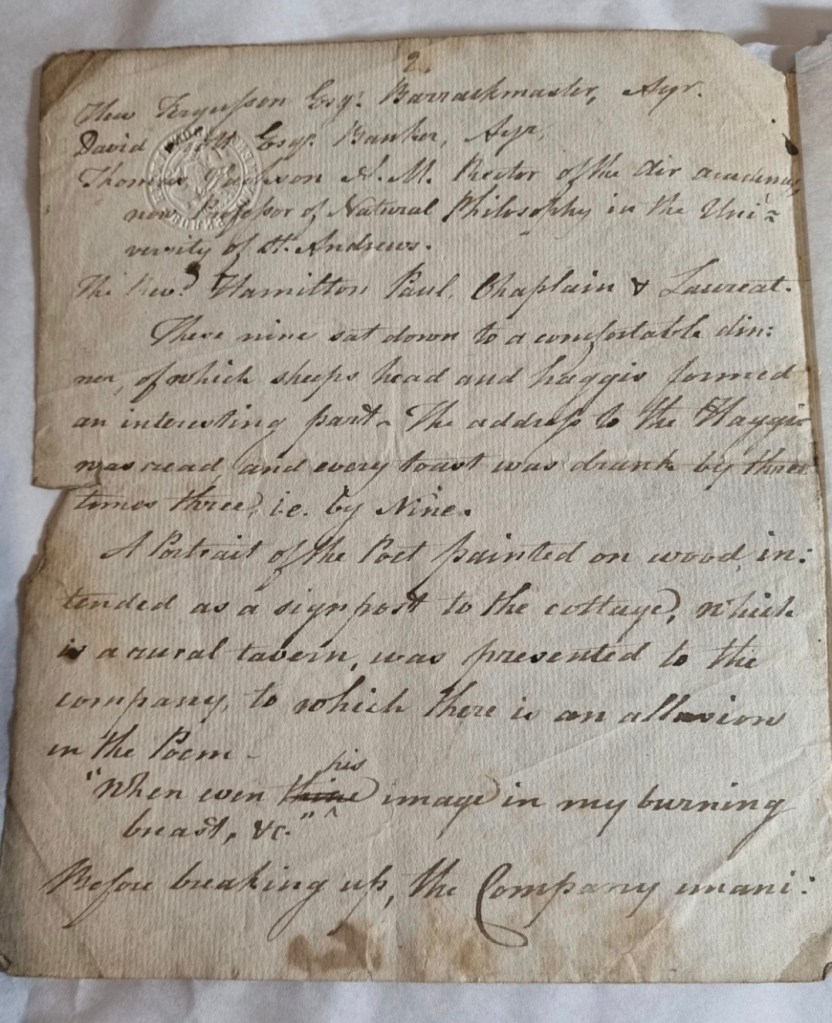

Haggis & the First Burns Suppers with Jennie Hood

Welcome to the first of a two-part special all about Burns Night.

Burns Night, celebrated on Robert Burns’ birthday, 25th January, is a worldwide phenomenon and I wanted to make a couple of episodes focussing upon the night, the haggis, but also the other foods links regarding Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns.

The episode is available on all podcast apps, but can also be streamed here:

Burns was born in Alloway, Ayrshire on 25 January 1759 and he died in Dumfries on 21 July 1796 at just 37 years old.

My guest today is food historian Jennie Hood, who has written an excellent article for the most recent edition of food history journal Petit Propos Culinares, entitled ‘A History of Haggis and the Burns Night Tradition’, so she is the perfect person to speak with on this topic.

Jennie Hood hails from Ayrshire, just like Robert Burns, and we talk about the origin of Burns Night, but we also talk about the medieval origins of the most important food item on the Burns supper plate – the haggis.

Things covered include the first English recipes for haggis, what makes a haggis a haggis (not as easy a thing as you might expect), Burns’s poem Address to a Haggis and what it tells us about haggises in Burns’s day and how the first Burns suppers started and gained such popularity, amongst many other things.

Follow Jennie on social media: Threads/Instagram @medievalfoodwithjennie; Bluesky @medievalfoodjennie.bsky.social; Facebook https://www.facebook.com/medievalfoodwithjennie

Company of St Margaret, Jennie’s late medieval and renaissance re-enactment group

Issue 133 of Petits Propos Culinaires

If you can, support the podcast and blogs by becoming a £3 monthly subscriber, and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, access to the easter eggs and the secret podcast, or treat me to a one-off virtual pint or coffee: click here.

This episode was mixed and engineered by Thomas Ntinas of the Delicious Legacy podcast.

Things mentioned in today’s episode

The Good Housewife’s Jewel by Thomas Dawson

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse (‘Haggas’ recipe p.291)

The Robert Burns World Federation

Address to a Haggis by Robert Burns

Suzanne MacIver’s recipe for haggis

Ivan Day’s recipe for hack pudding

The Philosophy of Puddings by Neil Buttery

BBC Countryfile January 2026 edition

Royal Births, Marriages & Deaths website (Channel 5)

Previous pertinent blog posts

Lamb’s Head with Brain Sauce (from Neil Cooks Grigson)

Previous pertinent podcast episodes

The Philosophy of Puddings with Neil Buttery, Peter Gilchrist & Lindsay Middleton

Neil’s blogs and YouTube channel

The British Food History Channel

Neil’s books

Before Mrs Beeton: Elizabeth Raffald, England’s Most Influential Housekeeper

Knead to Know: a History of Baking

Don’t forget, there will be postbag episodes in the future, so if you have any questions or queries about today’s episode, or indeed any episode, or have a question about the history of British food please email me at neil@britishfoodhistory.com, or on twitter and BlueSky @neilbuttery, or Instagram and Threads dr_neil_buttery. My DMs are open.

You can also join the British Food: a History Facebook discussion page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/britishfoodhistory

Happy New Year!

Well, cheerio 2025, it was nice knowing you, but it’s time to move on to 2026 – I must admit, I’m both glad and sad to see it go.

2025 was the year I took time off from writing books (writing two at the same time in 2024-5 required some time away). This doesn’t mean that I took a year off writing: I wrote several pieces for BBC Countryfile Magazine, including one about Plough Monday and Plough Pudding which will appear in the January 2026 edition of the magazine. There was the County Foods series for Country Life too, of course.

I worked with the Museum of Royal Worcester on another project about historic ices and the ways in which they were prepared and served. The previous project ‘Dr Wall’s Dinner’ won the Food on Display award at the inaugural British Library Food Season Awards 2025. I will be teaming up with Paul Crane (who you might remember appeared on the podcast in 2025) to give a talk about the history of sugar and the effect sugar production had on the porcelain manufactory at Worcester porcelain. This talk takes place online in March and will be free to attend. Keep a lookout on the Events page – I’ll update it when I know more details.

I made my first live television appearance in November on Sky News to talk about the history of mince pies – very scary, but I must admit, I did enjoy it!

I also contributed to the Channel 5 series Royal Births, Marriages and Deaths talking about the death of Henry I and his surfeit of lampreys – the episode will be shown in January or February 2026, so keep a lookout for it.

The podcasts have continued to go from strength to strength, and I really pushed hard in this last season (the ninth) of The British Food History Podcast to produce a really varied set of topics. Looking back on the data, the three most popular episodes were: Bronze Age Food & Foodways with Chris Wakefield & Rachel Ballantyne, Special Postbag Edition #6 and Shakespearean Food & Drink with Sam Bilton.

This year also saw the launch of the secret podcast for monthly subscribers.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription, where you will receive access to the secret podcast, a monthly newsletter and other premium content: follow this link for more information.

There was ‘Season B’ of A is for Apple: An Encyclopaedia of Food & Drink, too of course, which I co-host with Sam Bilton and Alessandra Pino, which is really gaining popularity now, so if you haven’t checked it out before, please do.

Perhaps the most exciting thing to happen this year was the very first Serve it Forth Food History Festival in October. It was an online event organised by Sam Bilton, Thomas Ntinas, Alessandra Pino and me. It was a fantastic day, and I’m so glad to have seen so many readers of the blog and listeners to the podcasts there. We all organised our own sessions and I was very lucky to have food writer and broadcaster Tom Parker Bowles as a guest. There was also a mini Christmas special looking at the darker side of Christmas and how food plays a role. The four of us are meeting up soon to discuss what will be happening for the next event.

The blog saw lots and lots of puddings this year: early modern black pudding, Gervase Markham’s white pudding, junket, Bakewell tart and a fancy Nesselrode pudding for Christmas. Sticking with frozen desserts, I also went somewhat experimental and made white pudding ice cream and blood ice cream, both of which were delicious!

I finally wrote up my recipe for Cumbrian Tatie Pot (informed by the episode of the podcast about black and white pudding). Another recipe I had been meaning to publish for you for ages was one for scones (not one in fact, but four) along with a post about their history. Other recipes included saffron buns, Yorkshire teacakes, lambswool and turkey & hazelnut soup.

Of course, I would be doing none of these things if it wasn’t for all of you fantastic people who read, cook, listen, watch and interact with me, so thank you all for your support, it really does mean a lot.

What about the coming year? Well I have already organised interviews for season 10 of The British Food History Podcast, A is for Apple will certainly be returning, and I will be beginning a brand new book in 2026 – I shall tell you about it as things develop.

Have a great 2026!

Neil x

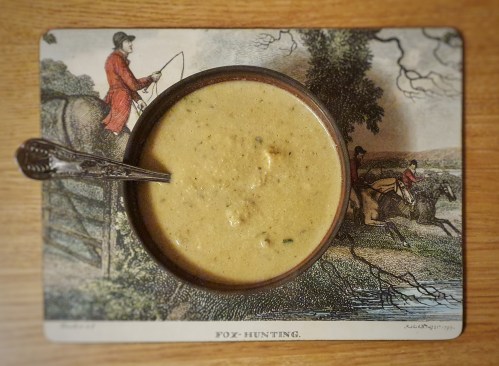

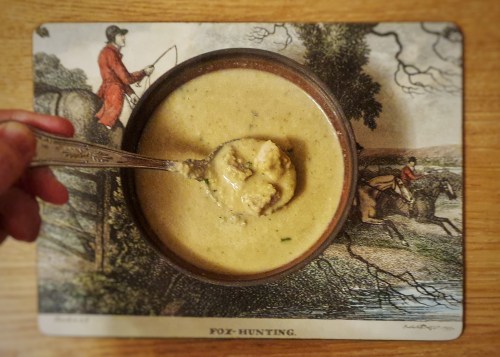

To Make Turkey and Hazelnut Soup (& Turkey Stock)

If you are not loving your leftovers at Christmastime, then you are missing a trick: it doesn’t have to be all dry turkey and cranberry sandwiches for the next week.

This is a really great recipe adapted from Jane Grigson’s English Food. I’ve made a few tweaks, and I have provided you with a method for making turkey stock. This recipe would work with leftover chicken, or even pheasant and partridge, or a mix of them.

Because it’s a leftovers dish, don’t worry if you don’t have all of the ingredients, though I would say it’s important to have at least three of the basic soup veg and one herb (fresh or dried). It doesn’t even matter if you don’t have any hazelnuts: almonds would work just as well, or you could miss them out entirely. Also, if there are any leftover boiled or steamed vegetables, or roast potatoes, you can pop them in before everything gets blitzed.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

This recipe makes many servings.

For the soup

2 to 3 tbs of fat: this could be butter, leftover fat from the roast potatoes or skimmed from the roast turkey juices

Basic soup veg, peeled, trimmed and diced, such as 2 carrots, 2 onions, 3 cloves garlic, white part of one or two leeks (keep the green parts for the stock), 3 sticks of celery

Herbs: 4 bay leaves, a small bunch of thyme or a tsp of mixed, dried herbs

1 tsp celery salt

1 bunch tarragon leaves, chopped

1 bunch parsley, chopped

1 medium potato, peeled and diced

1.5-2 L turkey stock

Salt and pepper

2 handfuls diced turkey breast (or whatever you have left)

100 g roast hazelnuts, roughly chopped

Leftover stuffing, cut into approx. 1 cm dice

150 ml cream

Heat the fat in a stockpot or large saucepan and add the diced soup veg and herbs, plus the celery salt. Stir and fry on a medium heat until things begin to turn golden brown. Add half of the parsley and tarragon plus the potato and continue to cook for another 7 or 8 minutes.

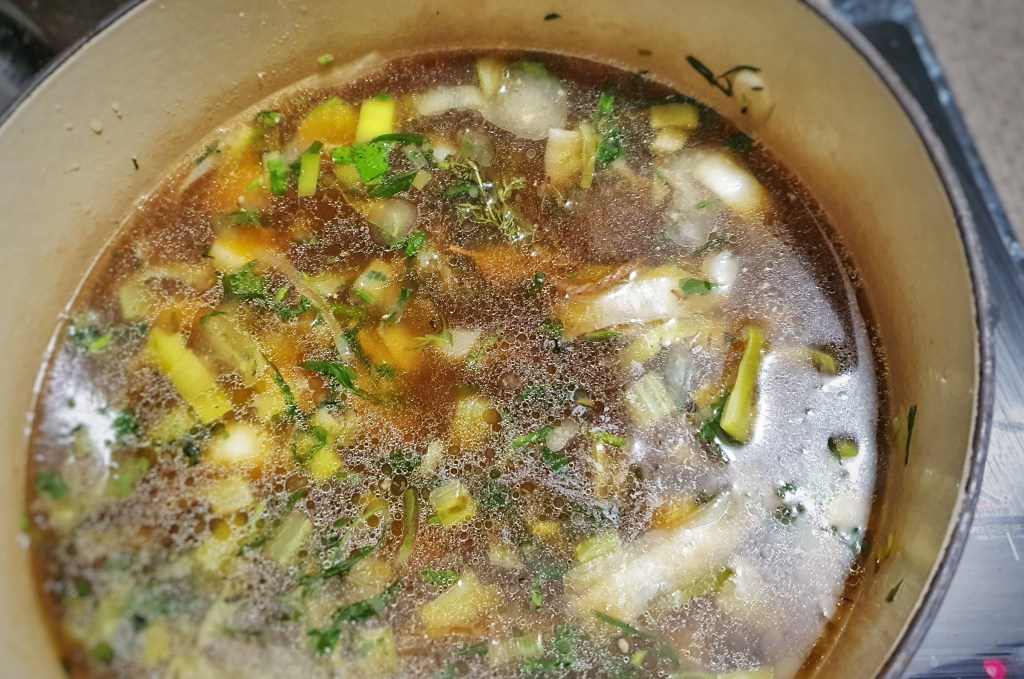

Pour in the turkey stock and bring the whole lot to a lively simmer, then turn it down to gently bubble until the vegetables are nice and soft, about 15 minutes.

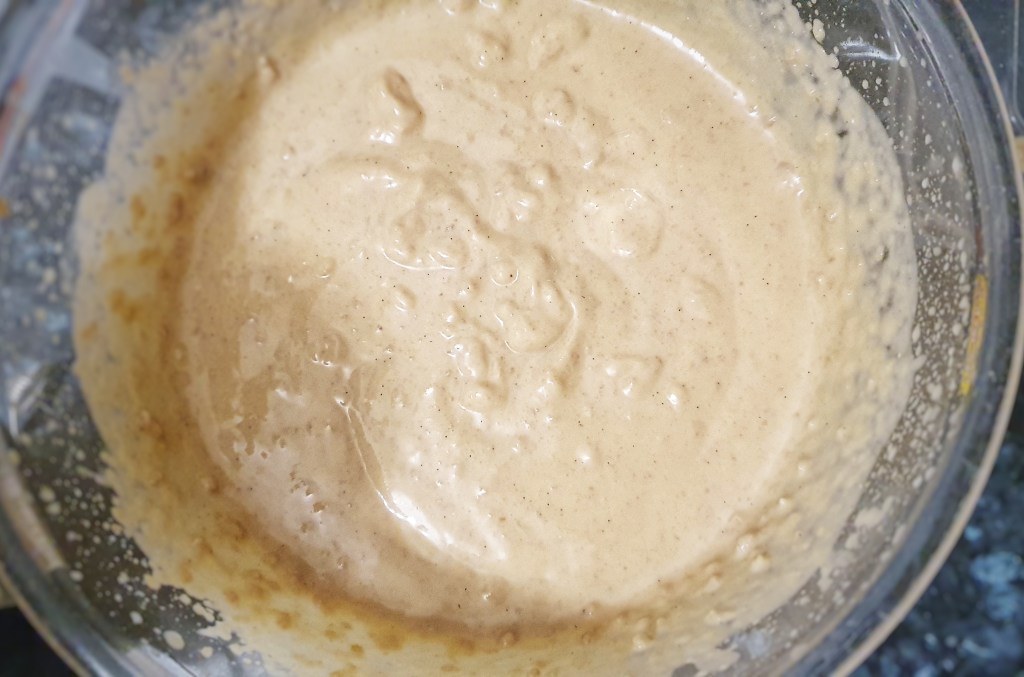

Taste, and season with salt and pepper at this point, then add the diced turkey and the hazelnuts. Simmer for a further 7 or 8 minutes, then allow to cool slightly before blitzing the soup in batches in your blender or food processor. Be careful here! Don’t overfill your blender, especially if the soup is still quite hot.

Return to a clean pan, bring back to a simmer, add the cream and the rest of the parsley and tarragon, as well as the diced leftover stuffing. Taste and season with more celery salt and pepper. Serve immediately.

For the stock

I keep vegetable trimmings and peelings in bags in my freezer for stock-making sessions such as these; you can, of course, use regular stock vegetables: celery, onions, carrots, leeks, etc.

Makes around 2 litres of jellied stock

2 tbs of fat or oil

The roast turkey carcass, broken into pieces – don’t be too thorough with removing the meat, leave some on.

Vegetable trimmings and peelings (avoid brassicas) or a mixture of stock vegetables: 2 carrots, 2 celery sticks, the green part of a leek or two, a couple of onions, a few smashed garlic cloves.

Aromatic herbs, e.g. 3 or 4 bay leaves, a small bunch of thyme and/or rosemary, parsley stalks

Aromatic spices, e.g. 1 tsp black peppercorns, 6 cloves, 1 tsp allspice berries, 2 blades of mace

1 tsp salt

Any leftover turkey juices or turkey gravy

Cool water to cover

Heat the fat or oil in a stockpot or pressure cooker and add the turkey carcass, the vegetables, the herbs, the spices as well as the salt. Stir and fry until both the turkey and vegetables are starting to turn a good, golden brown.

Add any leftover gravy and top up with water so that it barely covers the turkey and vegetables.

If cooking in a stockpot: bring slowly to a simmer, turn the heat over and let it cook very gently for two hours.

If cooking in a pressure cooker: bring to a simmer, when high pressure is reached, reduce the heat and cook for 25 minutes before turning off the heat and allowing the stock to depressurise.

If cooking in a slow cooker: transfer everything to your slow cooker (careful!) and cook on a high setting for 1 hour and then a medium setting for 2 more hours.

When the stock is ready, pass the whole thing through a strainer, pressing down on the cooked mush with the back of the ladle: we want as much flavour as possible. Let the stock cool down and then refrigerate. Skim away the fat before using.

Tip: If you need the stock straight away, you can skim the fat with a spoon, but a quicker method is to throw in a couple of handfuls of ice cubes. The fats immediately freeze to the exterior of the cubes, and can be lifted out before the ice has had the chance to melt.

Lambswool

Merry Christmas everyone!

It’s time for my annual Yuletide boozy drink post. This year: lambswool, a drink very much associated with the Wassail on Twelfth Night (the night before Epiphany, 6 January, and the last day of Christmastide). It has been drunk since at least Tudor times – I cannot find any descriptions prior to the late 16th century. It’s a type of mulled ale, and this description by Robert Herrick in his poem Twelfth Night: Or King and Queen (1648) is a very good one:

Next crowne the lowle full

with gentle lamb’s wool;

Adde sugar, nutmeg and ginger;

with a store of ale too;

and thus ye must doe

to make the wassaille a swinger.[1]

What Henrick doesn’t tell us is that there is cooked apple floating on the top which break apart, hence the name lambswool. These apples are, in the early modern period, generally roasted crab apples, so very sour in flavour, though in later recipes such as the lambswool described by Peter Brears in Traditional Food in Yorkshire, made in Otley, West Yorkshire in 1901, dessert apples are used. They were cored and cooked and floated in the drink, then fished out and eaten separately.[2] Spiced cakes and mince pies were also eaten.[3]

Many drinks were laced with rum or brandy and often enriched with eggs, cream or both,[4] such as this one here for ‘Royal Lamb’s Wool’, dated 1633: ‘Boil three pints of ale; – beat six eggs, the whites and yolks together; set both to the fire in a pewter pot; add roasted apples, sugar, beaten nutmegs, cloves and ginger; and, being well brewed, drink it while hot.’[5] Before the lambswool was poured into the Wassail cup sliced of well-toasted bread sat at the bottom. With the apple floating on top, this was basically a full meal. Nice and full, it was then passed around, everyone taking a sup from the communal bowl. I prefer to ladle it into separate glasses or mugs – and I am sure my guests would be pleased with this decision.

Lambswool drinking was not restricted to Twelfth Night, or even Christmastide, as this entry from Samuel Pepys’ diary dated the 9th of November 1666 informs us: ‘Being come home [from an evening of dancing], we to cards, till two in the morning, and drinking lamb’s-wool. So to bed.’[6]

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

I have to admit, I was unsure about the lambswool, but it was delicious. I think that it should come back, and it is certainly much, much nicer than bought mulled wine. Recipes don’t necessarily specify the type of sugar, but I think light brown sugar really complements the maltiness of the beer well.

A note on the beer: trendy IPAs and other craft beers are far too hoppy for this recipe – I think there’s a flavour clash, so make sure you go for a low-hop traditional brown ale. I used Old Speckled Hen (which is available to buy gluten-free, by the way). The best – and, dare I say it – most authentic choice would be an unhopped ale, but I have never come across one! Add cream and eggs if you think it matches your own tastes: I have to admit that as an eating/drinking experience, the creamy texture worked better with the pureed apple than the version without.

I used dessert apples for the wool, but you can use crap apples if you want to be true to the early modern period, or Bramley’s Seedlings, which do have the benefit of breaking down to a nice fluff. I discovered that it’s very difficult to get your apples to float on top, but this is not of great importance. Sam Bilton has an ingenious way of getting her apple puree to float though, and that is to fold a whipped egg white into the cooked apple puree.[7]

Makes 6 to 8 servings

6 small to medium-sized dessert apples

Caster sugar to taste (optional)

2 x 500 ml bottles of brown ale

120 – 140 g soft dark brown sugar

2 cinnamon sticks

8 cloves

1 tsp ground ginger

120 ml dark rum or brandy

4 eggs (optional)

300 ml cream (any kind will do; optional)

To serve: freshly-grated nutmeg

Start by making the apple purée: peel, core and chop the apples and place in a small saucepan with a few tablespoons of water, cover, turn the heat to medium, and cook until soft. If the apples don’t break down naturally, use the back of a wooden spoon. Add caster sugar to taste – if any is needed at all.

Whilst the apples are cooking down, pour the beer into a saucepan, add 120 g of soft dark brown sugar if making the non-creamy/eggy version, or add 140 g if you’re intrigued by it! Snap the cinnamon sticks and chuck those in along with the other spices. Turn the heat to medium and let it all get nice and steaming-hot; you don’t want it to boil, otherwise you’ll lose a lot of the alcohol. Leave for 10 minutes so the spices can infuse, then add the rum or brandy. Let it come back up to heat for another five minutes. If you don’t want to make the custardy version, the lambswool is ready, and it can be ladled out into glasses or mugs and top with a couple of spoons of the warm apple purée and a few raspings of freshly-grated nutmeg.

For the custardy version: after you add the brandy or rum, whisk the eggs and cream in a bowl, take the lambswool off the heat, and pour three or four ladlefuls of it into the cream and egg mixture, whisking all the time. Now whisk this mixture into the lambswool, and stir over a medium-low heat until it thickens. If you want to use a thermometer to help you, you are looking to reach a temperature of 80°C. Pass the whole lot through a sieve and into a clean pan, and serve as above.

Notes

[1] Herrick, Robert. Works of Robert Herrick. vol II. Alfred Pollard, ed., London, Lawrence & Bullen, 1891.

[2] Brears, P. (2014) Traditional Food in Yorkshire. Prospect Books.

[3] Brears (2014); Crosby, J. (2023) Apples and Orchards since the Eighteenth Century: Material Innovation and Cultural Tradition. Bloomsbury.

[4] Hole, C. (1976) British Folk Customs. Hutchinson Publishing Ltd.

[5] Though quoted in many places, I could not find the source of this recipe – but the reigning monarch was Charles I

[6] Diary entries from November 1666, The Diary of Samuel Pepys website https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1666/11/.

[7] Bilton, S. (2025) Much Ado About Cooking: Delicious Shakespearean Feasts for Every Occasion. Hachette UK.

Nesselrode Pudding

This delicious iced dessert, which was very popular in the 19th century at Christmastime, crops up in most cookery books of the time, and is described as ‘a quiet Victorian icon’ by Annie Gray in her excellent book At Christmas We Feast (2021).[1] It is associated with this time of year because of its main ingredient: puréed chestnuts, and it deserves a comeback.

According to Eliza Acton, the pudding was invented by the famous Marie-Antoine Carême,[2] but it is not the case. In one of her best (and most obscure) books, Food with the Famous, Jane Grigson informs us that it was actually ‘invented by Monsieur Mony, chef for many years, to the Russian diplomat, Count Nesselrode, in Paris.’[3] Annie Gray took the research step further: the first printed recipe appears in Carême’s book L’Art de la Cuisine Française. In the original French version, he tells us he got the recipe from Mony, but in the English translation, he claims he – Carême – invented it.[4] Odd.

Recipes do vary, though chestnuts are essential (unless you are Agnes Marshall, who asks – rather controversially – for almonds, in her Book of Ices[5]). Other ingredients include glacé and dried fruits, vanilla and maraschino liqueur – an essential. in my book, but some recipes suggest using brandy or rum as alternatives. There is a custard base, but the mixture is not churned like regular ice cream: this is a no-churn affair. It’s prevented from freezing to a solid block with the addition of airy whipped cream and Italian meringue.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Recipe

There are several stages to making this pudding, and you need to start making it at least two days before you want to eat it. Don’t let the making of egg custard sauces and Italian meringues put you off. However, a good digital thermometer and electric beater are essential.

Serves 8

For the pudding:

60 g chopped raisins or mixed fruit (currants, raisins and sultanas)[7]

60 g chopped candied peel or Maraschino cherries

80 ml maraschino

1 vanilla pod

300 ml single cream

3 egg yolks

160 g light brown sugar

160 g caster sugar

3 tbs/45 ml water

2 egg whites

300 ml whipping cream

440 g can or 2 x 200 g packets of unsweetened chestnut purée

To garnish: Maraschino cherries or candied chestnuts

For the custard sauce:

300 ml single cream or half-and-half whole milk and cream

50 g caster sugar

4 egg yolks

Around 25 ml maraschino (see recipe)

Soak the dried fruit and peel or cherries in maraschino overnight.

Next day, split the vanilla pod lengthways and scrape out the seeds and place both pod and seeds in a saucepan along with the single cream and heat to scalding point.

Meanwhile, put the egg yolks and light brown sugar in a mixing bowl, mix and then beat with a balloon whisk until it becomes a few shades paler. Pour in the hot cream by degrees, whisking all the time. Return the mixture to the pan and stir over a medium-low heat until it thickens – don’t let it boil, or you’ll get scrambled eggs – this should take about 5 minutes. If you want to use a thermometer to help you judge this, you are looking for a temperature of 80°C. Pass the mixture through a sieve into a tub, seal, cool and refrigerate until cold.

As it cools, make an Italian meringue: in a thick-bottomed saucepan, add the sugar and water. Place over a medium and stir until the sugar is dissolved, then bring it up to a boil. Insert your thermometer.

Meanwhile, put the whites in a bowl, ready to beat. When the temperature of the syrup hits 110-115°C, start beating the eggs to stiff peaks. When the syrup is 121°C, take the pan off the heat and trickle the syrup into the whites in a steady stream. Keep beating until almost cold – around 10 minutes – then cool completely. Whip the whipping cream until floppy.

Now the Nesselrode pudding can be assembled. Mix the chestnut puree into the cold, rich custard; you may need to use your electric beater to make the mixture smooth. If you like, pass the mixture through a sieve. Using a metal spoon, fold in the cream, then the meringue. Take your time – you don’t want to lose all of the air you have introduced to the meringue and cream. Strain the fruits (keep the alcohol) and fold those into the mixture.

Select your mould – a generous 2 lb/900 g loaf tin is best, but you can use a pudding basin, or anything you like, as long as it has a volume of around 1.5-1.6 litres – and line it with cling film. Gingerly pour or ladle the mixture, cover with more cling film and freeze overnight.

Now make the custard sauce as you normally would – there’s a full method here – flavour with the strained alcohol. Taste it and add more booze if desired. When it tastes just right, add an extra half shot. Cool, cover and refrigerate.

To serve:

Remove the pudding from the freezer 30 to 40 minutes before you want to serve it. At the same time, place the custard sauce in the freezer so that it can get really cold.

Turn out the pudding onto a serving plate, remove the cling film, clean up the edge with kitchen paper and garnish. If the pudding is a bit of a mess around the edge, pipe some whipped cream around it. Pour the ice-cold custard sauce into a jug and serve.

Note: to make nice, neat cuts, pour hot water into a tall mug or (heat-proof) glass and heat up a serrated knife; this heat and a gentle sawing motion should result in clean cuts.

Notes

[1] Gray, A. (2021) At Christmas We Feast: Festive Food Through the Ages. Profile.

[2] This earliest mention of the pudding in the many editions of Acton’s classic Modern Cookery was the 14th. Acton, E. (1854) Modern Cookery for Private Families. 14th ed. Lonman, Brown, Green, and Longhams.

[3] Grigson, J. (1979) Food with the Famous. Grub Street.

[4] Gray (2021)

[5] Marshall, A.B. (1885) The Book of Ices. William Clowes and Sons.

[6] Ibid.

[7] When I made the pudding for the blog, I decided to forego chopping the fruit, wanting nice, big, plump fruits. A mistake: the large pieces sank – rats!

Filed under Britain, Christmas, food, General, history, Nineteenth Century, Puddings, Recipes, The Victorians

White Pudding Ice Cream

After the roaring success of my blood ice cream, I decided to have a crack at making a white pudding ice cream too, using the flavours in Gervase Markham’s recipe.

The blood ice cream was great, but I didn’t call it black pudding ice cream, because I left out one important ingredient: oats. The flavour of wholegrain oats is key, so much so that without them, I don’t think I captured the pudding’s true flavour.

I wanted to change this with this ice cream, but the challenge was to capture the flavour of oats without any annoying frozen groats getting in the way. I decided to take pinhead (steel-cut) oats, soak them in milk and then squeeze it out to create an oat-flavoured milk. This worked really well. I added this to the usual milk and cream to make a custard, warmed it up with the spices and found that it naturally thickened to just the right consistency – all without egg yolks! The mixture froze very well and produced a super-smooth final product. As you can imagine, I was very pleased with this outcome.

Just like the blood ice cream, I soaked some dried fruit in sherry – currants and dates this time, as per Markam’s recipe and stirred them through at the soft-scoop stage of the churning process.

I served my white pudding ice cream with sweet black pudding that had been fried in butter and sugar. I then fried a slice of bread in the sugary and buttery juices and popped the black pudding on top with an accompanying scoop of the white pudding ice cream. It was decadent and delicious!

Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today and unlock lots of premium content, including bonus blog posts and recipes, my Easter eggs, newsletter and the secret podcast. Please click here for more information.