I’m continuing my mediaeval-themed posts with a somewhat infamous forgotten fruit: the openarse.

This unusual fruit is a member of the Rosaceae family which contains within its members familiar apples and pears as well as the less familiar, such as quinces, rosehips and sorbs; and like many of the cultivated varieties within this group, they made their way over here from Asia Minor. They quickly nestled themselves into the English mediaeval orchard, becoming an essential fruit crop.

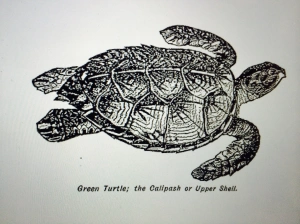

The openarse looks superficially like a russet apple’s withered twin; all squat, rough and green-brown. Turn it over and you’ll see how it gained its name. The calyces, usually small and tightly puckered on the underside of an apple or pear, are very large and lobular, protruding somewhat, giving it a definite rusty sheriff badge appearance. They also sometimes called grannies’ arses. Nice.

According to Jane Grigson in her Fruit Book, the ‘English name openarse, gradually and politely, …was superceded by the French-derived medlar.’ That said, the French also call them dogs’ arses. Trust them to be more vulgar us!

During the mediaeval period, medlars were widely cultivated in England, reaching peak production in the 1600s. They were a useful fruit because they store well, ripening up quite a while after picking. At first, however, they are rock hard, sour and terribly astringent. Picked in late autumn (some say to wait after the first frost) and stored in a cool, dark place, they begin to soften and sweeten. This controlled decay – called bletting – converts starch to the fruit sugar fructose and reduces the acid and tannin levels dramatically. It’s quite nice to see the fruits bletting at different rates and times; some blet on the tree, some take weeks post picking. You can see how this steady supply of ripening fruit would have been extremely important to mediaeval people during winter (see this post on mediaeval feast and famine for more information).

A bletted medlar

The traditional way to eat the fruit is to squeeze your openarse between your fingers so that the pulp can be either picked or sucked out. The medlar was considered very good for digestion and so would be taken after a meal with port (science is revisiting these ideas and has provided some experimental evidence that it is indeed the case). The taste is pleasant, lying somewhere between tart apple and sweet prune. Because the medlar was generally eaten in this way, recipes don’t tend to appear in old cook books; the only common recipe is for medlar jelly (which will be the subject of the next post). However, I did find one for a medlar tart in Thomas Dawson’s 1596 book The Good Housewife’s Jewel:

To Make a Tart of Medlars

Take medlars that be rotten and stamp them. Then set them on a chafing dish with coals, and beat in two yolks of eggs, boiling it till it be somewhat thick. Then season them sugar, cinnamon and ginger and lay it in the paste.

Thomas Dawson was a contemporary of William Shakespeare, and an openarse can be found in a Shakespeare passage. From Romeo and Juliet:

Now will he sit under a medlar tree,

And wish his mistress were that kind of fruit

As maids call medlars, when they laugh alone.

O Romeo, that she were, O that she were

An open-arse and thou a pop’rin pear!

A pop’rin pear, by the way, looks rather like a cock and balls. O! the camp bawdiness of it! I’m going to have to lie down.

Amusingly, the prudish Victorians replaced ‘openarse’ with ‘et cetera’, which – if you didn’t know of the replacement – makes no sense at all and, more importantly, spoils the joke.

FYI: Chaucer mentions openarses in the Canterbury Tales, and the earliest known use of the word goes right back to the 10th Century!

Colour plate from unknown source

Sourcing Medlars

After reading this, I expect you are simply dying to get your hands on some openarse yourself. This will be tricky; they are no longer grown commercially, so you’ll either have to plant one yourself or find a feral tree. If you live in the south of England this may not be an impossible task as many villages grew them in public spaces.

They are lovely trees – they grow untamed, sprawling in any direction they choose. They grow slowly, but still produce quite a large crop, so even a small tree would provide you with a decent glut of openarse. This is definitely the fruit tree for the lazy gardener.

As for me, I know the whereabouts of an ignored medlar tree in Manchester, but I’m keeping quiet about it; I don’t want all and sundry picking at my openarses now do I!?

I’ll stop now.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

![IMG-20160804-WA0002[1]](https://britishfoodhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/img-20160804-wa00021.jpg?w=300)