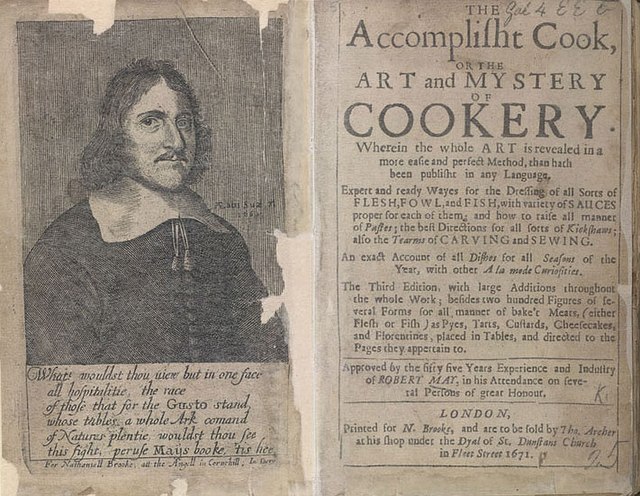

Earlier in the year, the fantastic Fruitpig (sponsors of the ninth season of the podcast) very kindly sent me some fresh pig’s blood so that I could try my hand at making some early modern black puddings, inspired by the recipes of Robert May, Kenelm Digby and Thomas Dawson. I made two versions: a savoury one and another sweetened with sugar and currants – both turned out to be delicious.

A few years ago I read (I forget where) that blood thickens upon heating just like egg yolks, and I had an idea in the back of my mind that blood ice cream might be possible to make, knowing already that the black puddings of the early modern period were often sweet.

Please that the sweet black puddings tasted good, I set about to see if I could find any British examples of blood ice cream or, at least, something similar. I couldn’t find anything. However, I did discover in the pages of Jennifer McLagan’s excellent offal cookbook Odd Bits, a blood and chocolate ice cream recipe, adapted from an Italian set dessert called sanguinaccio alla Neapolitana: little pots of set chocolate custard, thickened with blood instead of egg yolks.

Encouraged by the fact I knew it could be done, I went about adapting my black pudding recipe into an ice cream. I have a good, basic vanilla ice cream recipe that I’ve been using for years, which in turn is based on my custard recipe, and all I did was swap out the eight egg yolks for 200 ml of pig’s blood. Not convinced that the blood would thicken things sufficiently, I popped in two egg yolks for good measure. The milk and cream were flavoured not with a vanilla pod, but the same aromatics as the black pudding: pepper, cloves, mace and dried mixed herbs. I really wanted to include the currants, but knowing they would freeze hard into bullets, I thought an overnight soak in some sherry would work well – not unlike modern rum and raisin ice cream. I chose sherry because it’s the closest thing we have to sack, the popular fortified wine of the early modern period, and a common addition to recipes.

Well, I am very pleased to say that it was a great success. It was the richest ice cream I have ever eaten: luxurious, aromatic and with a very slight metallic tang. I ate a scoop with one of my early modern white puddings. What a combination!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Ingredients

300 ml milk

300 ml cream seeds

½ tsp bl peppercorns

1 tsp fennel

½ tsp cloves

2 blades of mace

1 tsp dried mixed herbs

200 ml fresh blood

2 egg yolks

160 g sugar

50 g currants

a few tablespoons of sweet or medium sherry overnight

Method

Pour the milk and cream into a saucepan. Crack the peppercorns and bruise the remaining spices in a pestle and mortar, and add to the milk and cream along with the dried herbs. Mix well, making sure everything has been submerged, and warm the mixture over a medium-low heat and bring everything to scalding point – i.e. just before the milk and cream boil.

Meanwhile, add the blood, egg yolks and sugar to a mixing bowl and whisk together well.

When the mix and cream mixture reaches scalding point, remove the pan from the heat and whisk in around a quarter of it into the blood mixture. When everything is incorporated, beat in the rest of the cream mixture, and pour the whole thing back into the saucepan.

Now keep whisking or stirring until the temperature reaches 80°C – you can tell this temperature is reached because the mixture thickens noticeably and coats the back of a spoon (check with a difital thermometer, if unsure). Take off the heat and pass the whole thing through a sieve into a clean bowl or tub. Leave to cool and refrigerate overnight. Soak the currants in sherry and leave those to macerate overnight too.

Next day, churn the mixture in an ice cream machine until a very thick soft-scoop consistency. As you wait, strain the currants (keep the sherry and drink it!). When the ice cream is almost ready, add the currants.

Pour the mixture into tubs and store in the freezer. Eaten within 3 months.