Cornish splits are soft and pillowy enriched bread rolls and were the original cakey element of the Cornish cream tea. Bread rolls such as these were – and indeed are– eaten all around the country. There were Devonshire chudleighs, Yorkshire cakes and Guernsey biscuits, for example. But it was the people of Devon and Cornwall who combined them with clotted cream and jam.

These light, fluffy rolls are enriched with butter and are made extra soft by being made with milk rather than water and are covered with a tea towel as soon as they come out of the oven – the captured steam softening the exterior crust. Once cooled – or better, just warm – the rolls are not cut open, but split open with the fingers, hence their name.

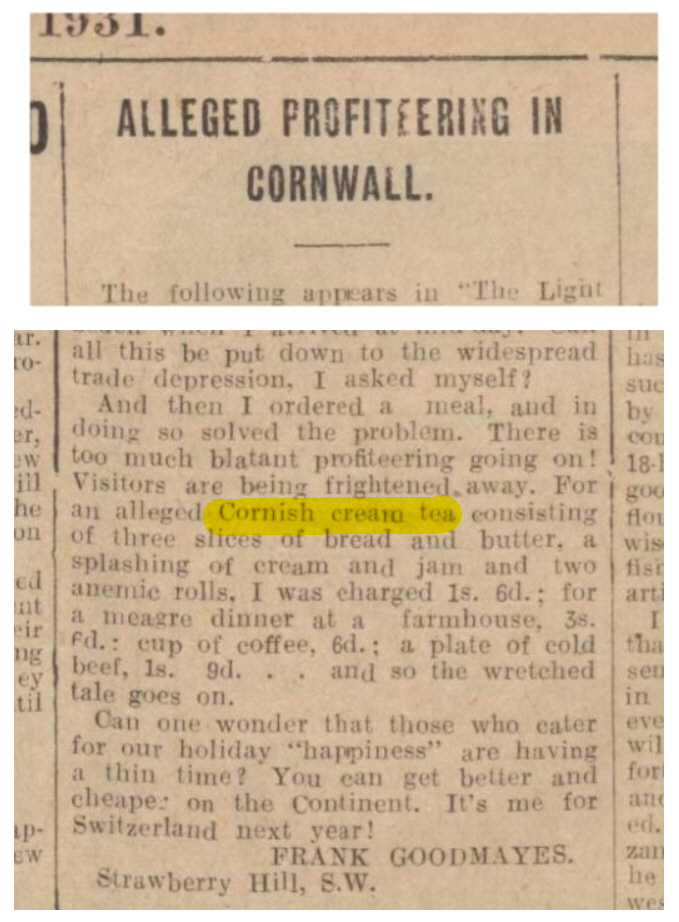

Of course, the cream tea as we know today it is made up a scone, clotted cream and jam. Some places sell them made with whipped cream, but that will not do. The phrase ‘cream tea’ meaning a scone/split with jam and cream (as opposed to tea with cream in) seems to be relatively modern – the earliest printed reference of one coming from a 1932 article in The Cornishman newspaper (see foodsofengland.com). The earliest mention of a combination of jam, cream and bread eaten together pops up in the Devon town Tavistock’s accounts dating from the tenth century!

Cutting from The Cornishman, Thursday 3rd September 1931 (foodsofengland.com)

Some establishments in Cornwall still serve a split instead of a scone in their cream teas, but they are few and far between. Many folk reckon that the split is superior to the scone in a cream tea, the scone winning out by virtue of it being much quicker and easier to make. The Devonians apparently turned to scones before the Cornish, presumably because Cornwall is more cut-off. So, we have a situation where the rivalry between the two lands can be stoked. The Cornish can claim they invented the cream tea because they invented the split, but the Devonians can claim they invented it because they came up with the cream tea we think of today.

The bakery where I grew up in Pudsey, West Yorkshire sold Cornish splits filled with whipped cream, thin seedless raspberry jam and lots of icing sugar. I used to love them, so I was keen to make them myself and have a proper Cornish cream tea.

This enriched dough is a little trickier to work with than regular white bread dough, but you can make it by hand without things becoming too much of a horrible sticky mess. I prefer to use the dough hook these days I must admit. I use strong bread flour to gain a nice rise, but older recipes use regular plain flour; feel free to use it too, but whilst your splits will be more historically authentic, they will be less light for it: your choice!

Makes 12 splits:

500 g white strong bread flour

8 g instant yeast

10 g salt

60g caster sugar

75 g softened butter

280 g warm milk

I’ve written before about making and forming bun dough in more detail before, so if there’s too much brevity here, click this link.

Mix the flour, yeast, salt, sugar in a bowl. Make a well and add the butter and then the milk. If you have a food mixer with a dough hook, mix slowly to combine, then turn up to speed 4 and knead for around 6 minutes or until the dough has become tight and smooth and no longer sticky.

You can of course do all of this by hand, using a little flour for kneading at first until the dough loses its stickiness.

Using your hand, form the dough into a tight ball, pop in a lightly oiled bowl and cover with cling film or a damp tea towel. Leave somewhere warm until it doubles in size, which could take 90 minutes depending upon the ambient temperature.

When ready, divide into 12 equal sized pieces, form them into balls and arrange on a baking sheet. Cover with a large plastic bag or tub and wait for them to prove. Once doubled in size again – it should take much less time than the first rising – place in a cold oven and turn it to 200°C. Bake for 25 minutes, but if at any point, the splits look like they getting too brown, turn the temperature down to 175°C.

When ready, remove from the oven to cooling tray and quickly place clean tea towels over the buns to prevent them crisping up.

When cold, you can sprinkle with sugar if you like, then slice or split and fill with jam and cream.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

References:

The Cornish split, original cream tea accompaniment, Cornwall Live website, www.cornwalllive.com/whats-on/food-drink/cornish-split-original-cream-tea-1336003

Good Things in England, Florence White, 1932

English Bread & Yeast Cookery, Elizabeth David, 1977

Classic Meals: Cream Tea, Foods of England website, http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/creamtea.htm

The Taste of Britain, Catherine Brown & Laura Mason, 1999