I’m carrying on the medieval almond milk theme (I will move away from this topic, I promise) with another post on what could be described as mediaeval England’s national dish – blanc mange. Blanc mange – literally white food – was a simple stew of poultry and rice poached in almond milk. Over the centuries, it evolved into the wobbly dessert we know and love (or hate) today. In France almond soups thickened with rice or bread are still eaten, so it appears that the blanc mange diverged into two different dishes: cold pud and creamy soup.

Blanc mange wasn’t just popular in England, but over the whole of mediaeval Europe. It began life as a Lent dish of rice, almond milk and fish such as pike or lobster, but people liked it so much that it was eaten at every meal, where the fish could be substituted with chicken or capon. Outside of Lent it could be flavoured with spices such as saffron, ginger, cinnamon and galangal, seasoned with verjuice, sugar and salt. It is thought that the dish originates from the Middle East, the part of the world we imported rice and almonds.

It’s worth mentioning that although a Lent dish, no commoner could afford this meal even in its most basic form– imported rice and almonds were very expensive, as were farmed chickens. This was commonplace food for the richer folk of society.

Here’s an example of a blanc mange recipe from around 1430:

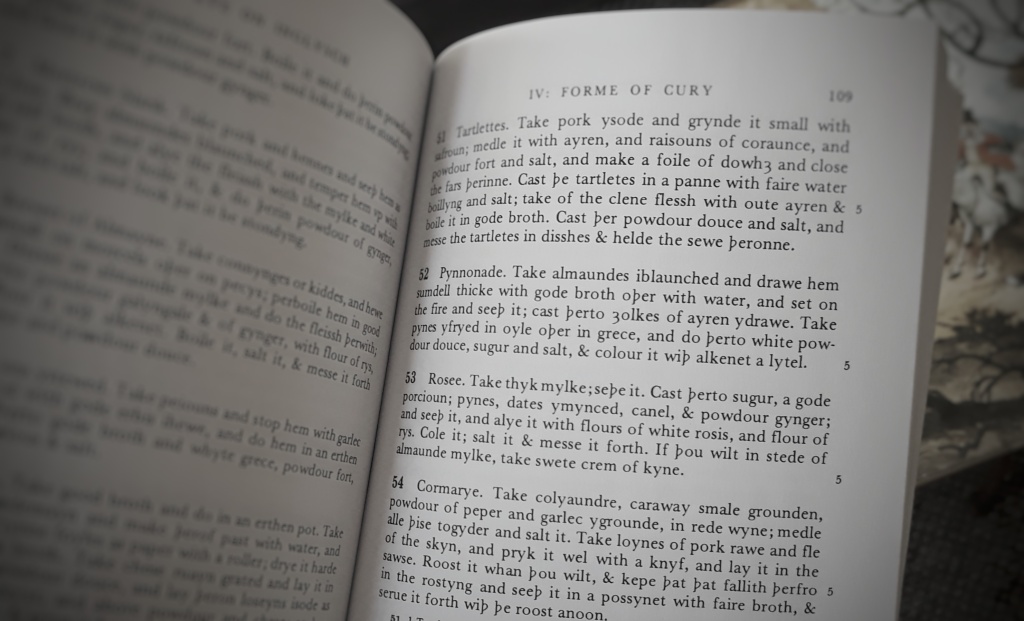

For to make blomanger. Nym rys & lese hem & washe hem clene, & do þereto god almande mylke & seþ hem tyl þey al tobrest; & þan lat hem kele. & nym þe lyre of þe hennyn or of capouns & grynd hem small; kest þereto wite grese & boyle it. Nym blanchyd almandys & safroun & set hem aboue in þe dysche & serue yt forþe.

This recipe seems to be for a blanc mange served cold or warm; the rice is cooked in the almond milk and cooled while the capon or chicken is poached separately. Saffron and almonds are sprinkled over the dish before serving.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

I’ve looked at a few recipes and they don’t really change over the next two hundred years – always chicken or fish, rice and almond milk and a few mild spices, sometimes served hot, sometimes cold and often adorned with slivered almonds fried in duck or goose fat and a sprinkle of sugar, all before being served forth. They also seem extremely bland with most recipes containing no spices at all. That said, many of our favourite foods are bland: white bread, mashed potatoes, avocados and mayonnaise all belong in the bland club, so bland does not equal bad. In fact, bland food is usually comfort food, and I strongly suspect that this is what is going on here, a bland white food, served at every meal no matter how grand. Blanc mange was mediaeval comfort food, the macaroni cheese of its day!

The blanc mange went from a chicken and rice dish to wobbly pudding somewhere around 1600 it seems. A 1596 recipe uses capon meat, ginger, cinnamon and sugar, and is pretty much identical to the recipes from 1400, but then I find in Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book of 1604 that she gives instruction for a cold sweet. She describes a moulded dessert set with calves’ foot jelly (i.e. gelatine), almonds, rice flour, rosewater, ginger and cinnamon.

Mediaeval Blanc Mange

I’ve combined the methods of several recipes from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The important thing to remember is that mediaeval almond milk would have contained sugar, salt and a little rosewater, so if you want to use the modern shop-bought stuff, you might want to add a little of all three for authenticity. Alternatively, you can have a go at making some yourself.

The spices I went for were ginger and cinnamon, but you can add white pepper, galingale and saffron too if you like.

The only thing I have done differently to the original recipes is to leave my chicken on the bone; bones stop the chicken drying out in the cooking process and flavour the dish.

1 L mediaeval almond milk flavoured with a few drops of almond extract

1 chicken jointed into 8 breast pieces, 4 thigh pieces and 2 drumsticks, skin removed

3 tbs duck or goose fat

white rice measured to the 300 ml line of a jug

½ tsp each ground cinnamon and ginger

1 ½ tsp salt

small handful slivered almonds

Demerara sugar and more salt for sprinkling

Pour the almond milk in a saucepan and heat up to almost boiling. Meanwhile, in a large saucepan melt one tablespoon of the goose or duck and when hot, tip in the rice. Stir to coat the rice grains in the fat, then add the spices and salt. Add the chicken pieces and hot almond milk and stir just once more.

Turn the heat down to low, place on a lid and simmer gently for 25 minutes.

When the time is almost up, fry the slivered almonds in the remaining fat until a deep golden-brown colour.

Serve the chicken and rice in deep bowls with the almonds, salt and sugar sprinkled over.

There you go, pretty easy stuff really. And the verdict? Well, it was quite bland, but pretty tasty with all of the adornments, and the flavours developed a lot over night when I reheated some. The sugar wasn’t as weird tasting as you might expect, and the mild scent of rose water really lifted the dish. The almonds fried in duck fat were amazing, and I’ll certainly be stealing that idea. Will I make it again? Probably not, I must admit, but it was an interesting experiment. Next post, I’ll give you a very easy recipe for a proper dessert blancmange, one of my favourite things to eat. Until then, cheerio!