Round about the cauldron go;

In the poison’d entrails throw.

Toad, that under cold stone

Days and nights has thirty-one

Swelter’d venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i’ in the charmed pot.

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble!

William Shakespeare Macbeth, Act 4, Scene 1

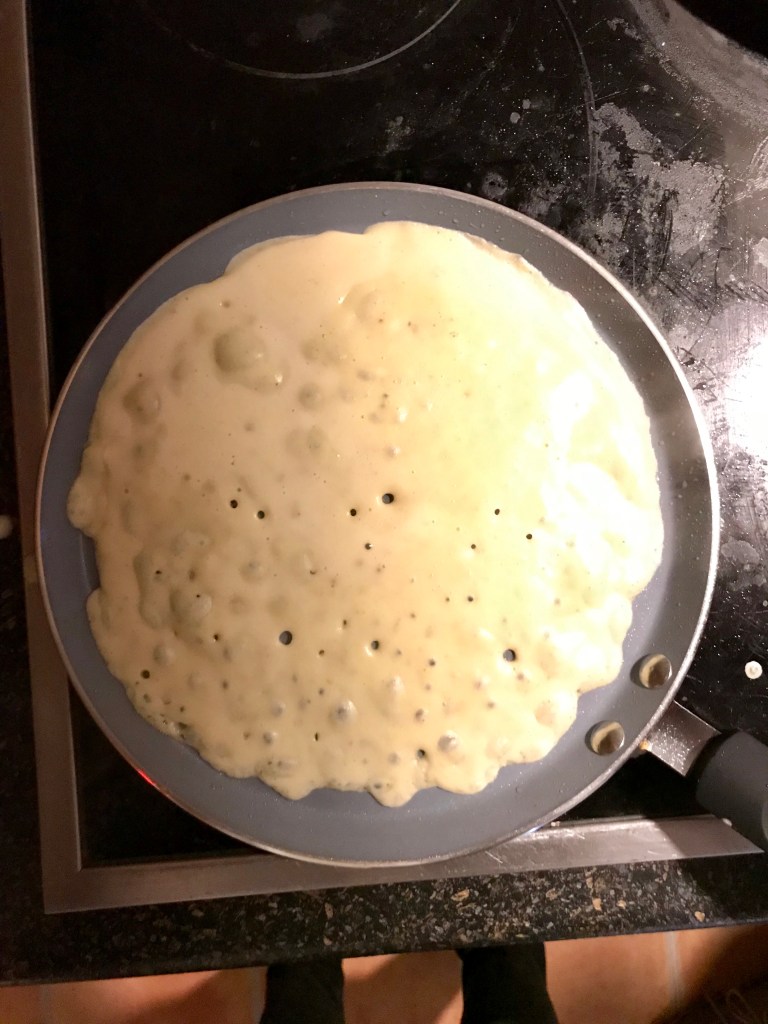

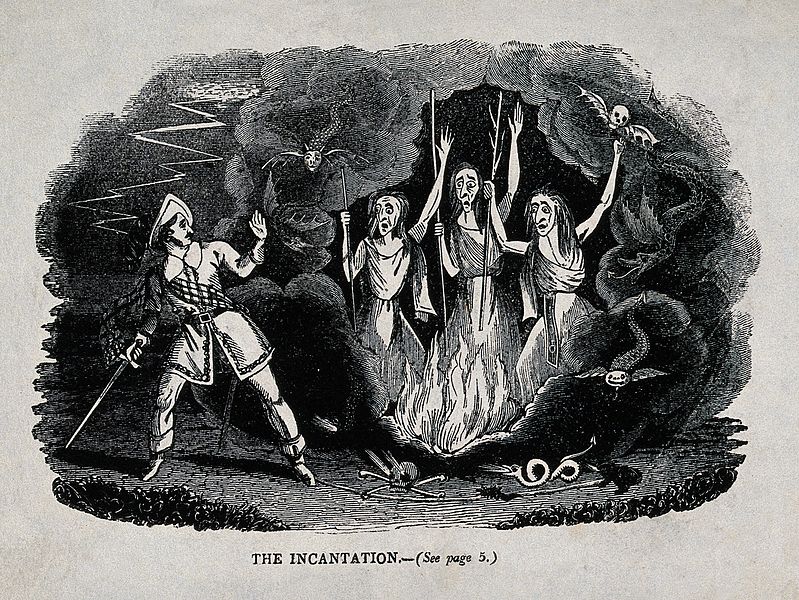

As it’s Hallowe’en I thought that I’d write a little post all about cauldrons, because of course along with a broomstick, pointy hat, black cat and warts it is a must-have for any witch worth their salt at this time of year.

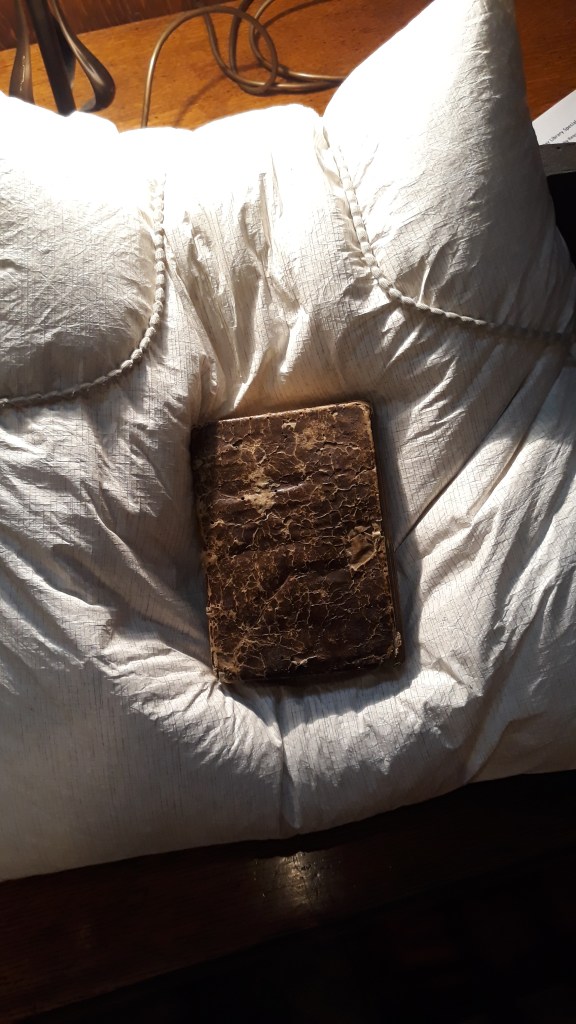

Let’s start off with what a cauldron is, just on case you are unfamiliar with them. They are large, rounded cooking pots that are suspended over a fire by a chain or on support legs in the centre of the fire, and they have been used all across Europe since the first millennium BCE. One of the oldest ever found was excavated in Battersea and is therefore known as the Battersea Cauldron. It made up of bronze sheets melded together and is huge. It has been described as “one of the largest and most sophisticated metal objects of the day” and is estimated to be 3000 years old, and it obviously got some use judging by the number of reparation patches it has covering its surface. Whatever size your cauldron was, it was an expensive bit of kit and built to last, so it is more unusual to find out without patches. Precious items such as this were passed down through the generations and the “man who owned an iron cauldron” says Dorothy Hartley, “had a definite standing above those who cooked only in small pots and pans.”

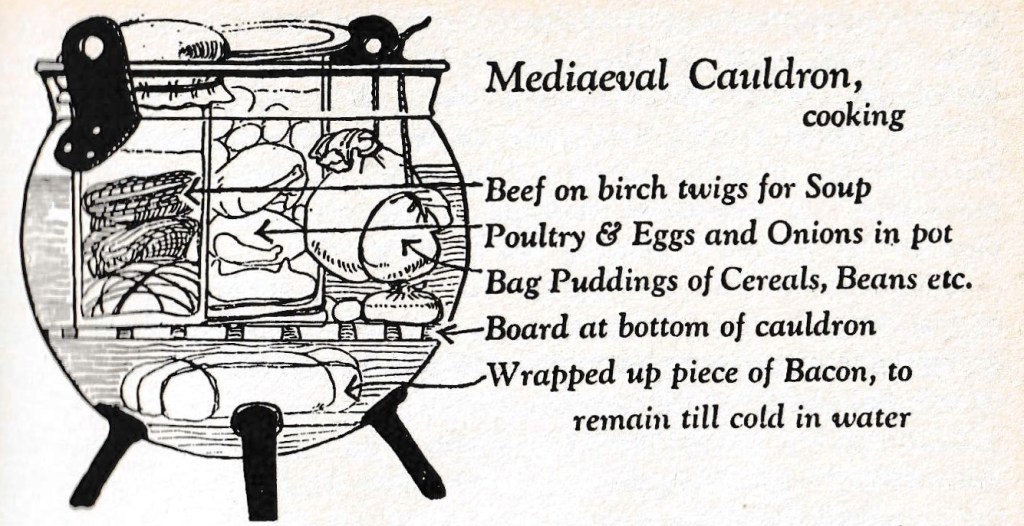

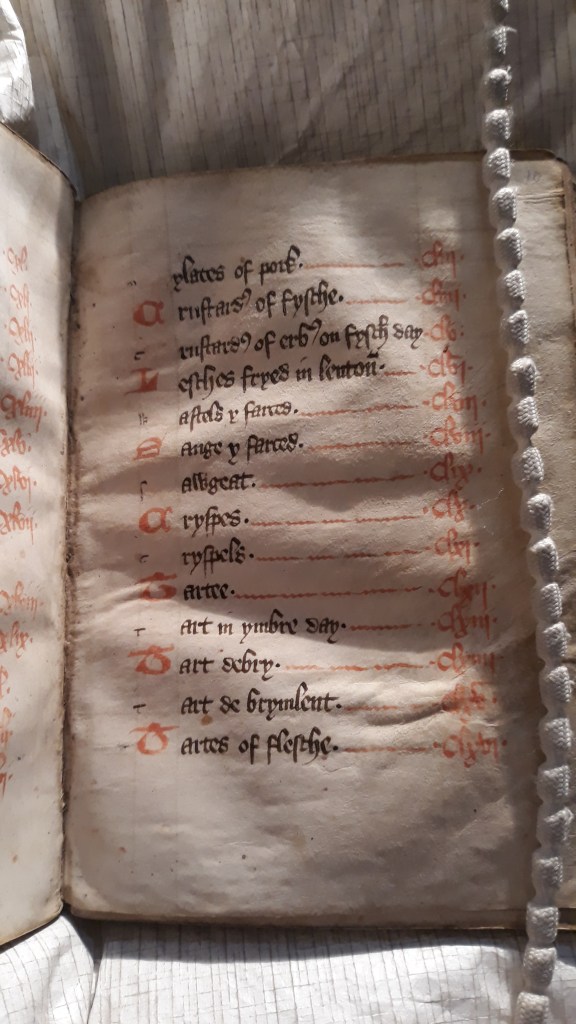

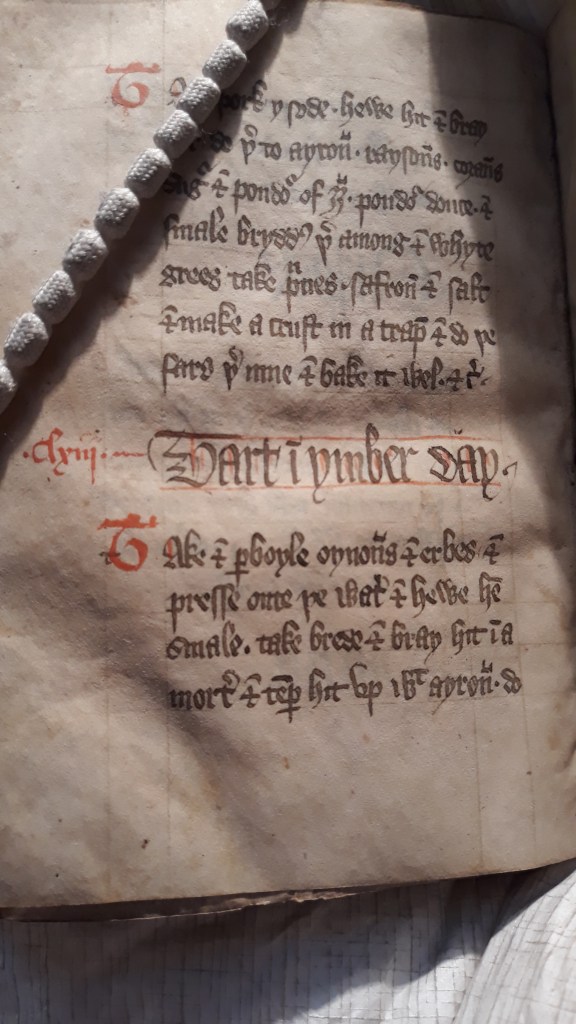

You may be thinking that a selection of pots and pans might be preferable to a massive cooking pot because they give you more options and you don’t have to make giant vats of food all the time, but a cauldron is surprisingly versatile and was rarely used for just cooking great big broths with bones bobbing about the surface. No, the cauldron was in fact the complete cooking and hot water system; take a look at this wonderful illustration from Ms Hartley’s excellent books Food in England:

You can see here how the cauldron was actually compartmentalised and filled with a whole variety of foods. At the base is a large joint of meat that required long cooking, usually wrapped in a flour paste and the tied up with cloth, then sat on that were wooden slats upon which all sorts of things were sat. There would have been some suet puddings wrapped in cloth simmering away, as well as bag puddings made up of peas, beans or cereal grains such as the classic pease pudding. If you did want to make some hearty stew, you placed your ingredients in earthenware jars, filled them with stock or water, covered them tightly and poached it in the cauldron water. This gentle way of poaching meat produced deliciously juicy cuts of meat; in fact, one cauldron found in Warwick Castle bore the legend: “I give meat good savour.” Often the meat was jointed and sat in a large jug, to produce old British classics such as jugged hare (or rabbit, I’ve also seen recipes for jugged kippers and jugged peas). Dorothy illustrates some beef tea being made where the meat is sat in its jar on top of some birch twigs, preventing the meat from sticking to the bottom. I love little details like those. You had to be very careful cooking like this though because those sealed pots acted like pressure cookers and were prone to exploding!

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription: follow this link for more information.

Aside from all of this, the cauldron also provided the washing water and bathwater. “I hope” says Hartley, “you now understand that because there was only one cauldron on the fire there was not one thing for dinner.”

Cauldrons were such important and precious items that they were even found in burial sites such as the Baldock Burial, a Bronze Age burial site in Hertfordshire, where a whole plethora of things were found including a cauldron complete with joints of meat, ready to sustain the dead as they journeyed to the Afterlife. Pagans revered them and they became symbolic of death and resurrection, often being buried in near or bogs and rivers, locations they considered to be domains of both the living and the dead.

Because they were imbibed with magic, they appear in several myths and legends; for example, the Irish god Dagda owned a cauldron that did not just magically produce food but also cured disease, healed wounds and brought the dead back to life. There was also a Cauldron of Knowledge that told you everything you wanted (and did not want) to know. There are plenty of Welsh and English stories that involve cauldrons too (though I haven’t come across any Scottish ones for some reason).

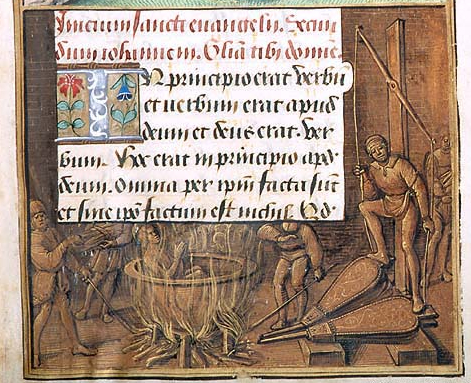

Cauldrons of course sat upon flames and were extensively found in medieval and Tudor Christian art to depict what might happen to you if you went to Hell. One example depicts Dives – a rich man Jesus tells us of in the New Testament, who was very rich but would not share his food with a poor beggar. He is shown “tormented with thirst stewing forever in one of Hell’s capacious cauldrons.” Another manuscript knows as the Hours of Henry VIII clearly shows St. John the Evangelist sat in cauldron of boiling oil looking pretty chilled out and happily preaching whilst being tormentind by his captors. He would be later be miraculously preserved in the oil rather like, one supposes, like some nice comfit duck legs.

So there we go, I hope you have enjoyed my brief history of cauldrons and appreciate that they are not just for witches…or Hallowe’en!

References

‘Cauldrons and flesh-hooks: between the living and the dead in ancient Britain and Ireland’ by Jennifer Wexler & Neil Wilkin, The British Museum Blog https://blog.britishmuseum.org/cauldrons-and-flesh-hooks-between-the-living-and-the-dead-in-ancient-britain-and-ireland/

Food in England (1954) by Dorothy Hartley

Hours of Henry VIII, MS H.8 fol.7 (c.1500) The Morgan Library & Museum http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/13/77089

The Medieval Cook (2009) by Bridget Henisch

‘Vessels of Death: Sacred Cauldrons in Archaeology and Myth’ (1998) by Miranda J Green, The Antiquaries Journal, vol 78, pp. 63-84